Key messages:

- The September 2025 protests in Nepal and the use of Discord to elect an interim prime minister show how, in the absence of institutional channels, digital platforms can assume functions of political legitimacy.

- This case confirms that the prevailing logic of social media (based on algorithms for selecting individualised content and the centrality of the visual) tends to fragment public conversation and reinforce dynamics that favour structural effects such as polarisation, the circulation of misinformation and political ephemerality, which were also visible in the Nepalese process.

- Bluetooth, which seemed to be a technology whose uses had been exhausted, took on a revolutionary role in Nepal by enabling meshnetworks capable of sustaining communication without the Internet, complemented by the massive use of VPNs in the face of blockages.

- This experience does not transform the structural role of platforms, but it does offer clues as to how consensus-oriented redesigns could strengthen citizen autonomy in the digital public sphere.

Analysis[1]

1. An unprecedented case

In September 2025 Nepal experienced a wave of protests that shook the country and led to the resignation of Prime Minister Khadga Prasad Oli, the burning of the National Assembly and the imposition of a military curfew in the capital. More than 70 people died in clashes with the police during a social uprising that combined several factors: outrage over corruption and inequality, and rejection of the government’s digital control measures.

With the main social networks blocked, tens of thousands of young people moved the political debate to Discord, a messaging app associated with the world of video games. In a matter of days, this space became a kind of digital convention where programmes were discussed and even the name of an interim prime minister, former judge Sushila Karkiv, was proposed.

The fact that a platform designed for conversation among gamersbecame the central stage for national politics, receiving legitimacy from the military, marks an unprecedented episode.

In the first half of fiscal year 2025, Nepal’s real GDP grew by approximately 4.9%, but more than 20% of its population of 30 million still live below the poverty line and youth unemployment remains at around 20%. Income inequality, with a Gini index close to 30 points,has declined slightly compared with a decade ago, although significant gaps remain between urban and rural areas and between social groups. The lack of productive diversification pushes a large part of the working population to seek opportunities abroad: around 7.5% of Nepalese citizens work outside the country, mainly in the Gulf States and Malaysia. As a result, remittances account for more than a quarter of GDP and sustain domestic consumption, but at the same time generate a strong dependence on external factors and the stability of international labour markets.

Precisely because of these vulnerabilities and dependencies, Nepal has become an example of rapid economic digitisation, with a swift expansion of electronic payments, in response to the lack of an inclusive financial system and dependence on remittances.

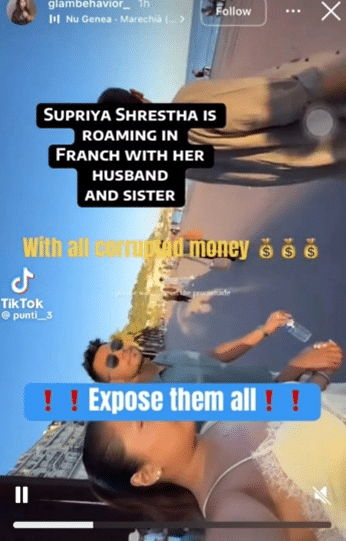

In this context of inequality, in mid-2025 videos of the so-called #NepoKids, young people from wealthy political and business families showing off their vacations in luxury destinations, imported cars and designer clothes, went viral on TikTok and Instagram. For many young people, these videos were the spark that turned accumulated discontent into open outrage.

The government banned 26 social media and messaging apps, including Facebook, Instagram, YouTube and X. The measure sparked unprecedented youth protests, leaving dozens dead and forcing the prime minister to resign. Parliament was paralysed and the country entered a power vacuum. The decision to block the platforms was officially justified by their failure to comply with a prerequisite for registration in Nepal, imposed on large technology companies months earlier. The government claimed that these companies were operating without local oversight, which posed a problem of digital sovereignty and content control. However, the ban was perceived as an attempt to silence the wave of outrage.

Having social media is not a right, but banning them does violate one, especially in countries with a large diaspora such as Nepal, where social media are the only means of communication with family and friends abroad.

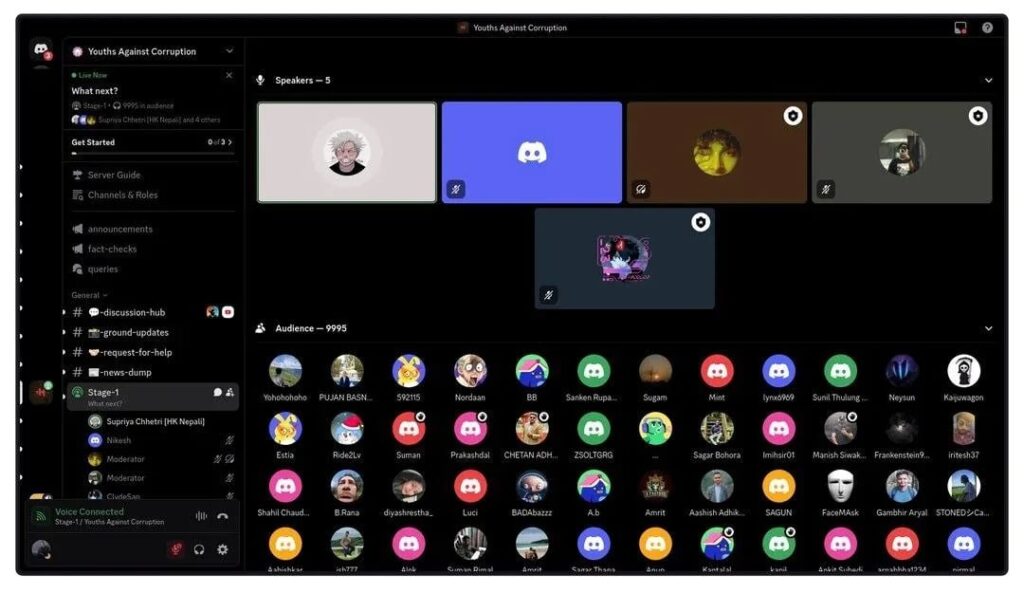

The public response then took an unexpected turn. Discord became the main space for political deliberation. More than 100,000 people joined the Youths Against Corruption server, where programmes were debated, candidates were presented, and open votes were organised and broadcast on local media.

Figure 1. Discord server where the country’s political future was debated

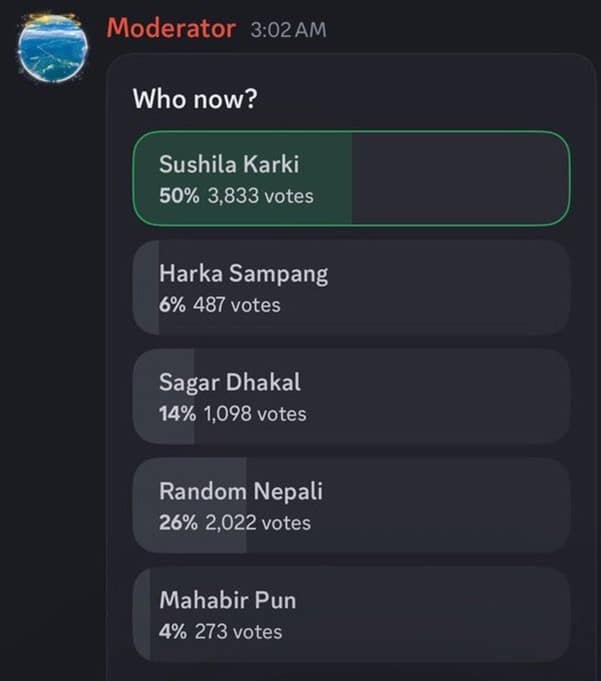

From this process, the former judge Sushila Karki emerged as the consensus candidate, a proposal that was recognised by military leaders and the president, who accepted the result as a legitimate way out of the crisis. Karki was sworn in as interim prime minister, becoming the first woman to hold the position.

Figure 2. Discord poll in which the new interim prime minister was elected with 50% of the votes

This episode raises the question: are we witnessing a temporary exception to the trend in which social media erodes social cohesion and democratic functioning or the beginning of a change of course that could open up new possibilities?

2. The dominant logic on social media

This process of digital deliberation should not be interpreted as a structural transformation of the political role of digital platforms. The dominant pattern (or, in the terms of the Prosocial Media article, its ‘pathologies’) remains very different.

Two features of social media show the extent to which the case of Nepal fits into this dominant logic:

- Individualised feeds using ranking algorithms. Each user receives a different selection of content, ordered according to what generates the most interaction. This fragments the experience and turns political conversation into a sequence of isolated perceptions. In Nepal young people saw a constant stream of symbols of outrage on their screens, such as the #NepoKids videos, which reinforced the idea of a widespread consensus against the elites. Other segments of the population, on the other hand, barely understood the sources of young people’s frustration.

Figure 3. TikTok video calling for exposure of the lifestyle of young people from Nepal’s economic and political elites

- Primacy of the visual and the emotional. Platforms such as TikTok and Instagram are designed to privilege images and videos that produce an immediate reaction. If the protests in Nepal reached every smartphone on the planet, it was because of the viral spread of scenes such as the Parliament in flames or ministers being thrown into the river.

Figure 4. TikTok video showing the finance minister being thrown into the river, chased and assaulted

Figure 5. TikTok video of the National Assembly in Kathmandu on fire

These two design elements give rise to three structural problems that are not unique to Nepal, but rather the norm in the contemporary digital ecosystem: polarisation; disinformation; and political ephemerality.

2.1. Polarisation

Political polarisation mediated by digital platforms is a widely documented phenomenon globally. Personalisation algorithms tend to lock users into like-minded bubbles and give greater visibility to extreme content. The circulation of memes and political messages occurs mainly in homogeneous communities, which reduces exposure to divergent perspectives.

For instance, following Facebook’s 2018 update that prioritised ‘meaningful social interactions’, surveys in Italy recorded an increase in ideological and emotional polarisation. When social interaction signals (such as likes and shares) are weighted more heavily, extreme content easily climbs to the top of feeds.

On 6 August 2025, just over a month before the outbreak, Instagram introduced the ‘repost’ feature, similar to TikTok’s, which allowed for the rapid dissemination and amplification of posts. The Nepalese magazine Himalmag identified this development as a milestone in the chronology of events that led to the protests. According to Himalmag, the ability to share posts instantly facilitated the mass dissemination of memes and political messages, amplifying the perception of polarisation in a context already marked by mistrust.

An experimental study with Facebook users during the 2020 US elections showed that removing reshares from feeds substantially reduced exposure to political news, including unreliable content, as users will tend to see more content shared by people they follow. It also decreased the number of clicks, reactions and visits to partisan news, and led to a decline in users’ political knowledge. However, the treatment did not change ideological polarisation or individual political attitudes.

Social media design decisions must be tested in electoral situations, protest scenarios and everyday life: stress tests that allow to anticipate their effects in different political and social contexts.

2.2. Disinformation

Disinformation has become a structural feature of the global digital ecosystem. Ranking algorithms prioritise content that generates immediate reactions, which favours the virality of false content.

In India, for instance, around 13% of images shared in WhatsApp groups were disinformation content. Furthermore, images and videos are more difficult to verify than text. Although advances in computer vision are beginning to improve automatic detection capabilities, they do not surpass text filters. A study by Texas A&M shows that on Facebook, the main source of disinformation is not fake articles on external websites, but imagescirculating directly in the feed.

In Nepal, according to the Center for Media Research (CMR-Nepal), between March 2020 and July 2024, 408 fact-checking reports on misinformation were published. Up to 56% of the misinformation originated on social media, while 36% came from print or online media. A 2021 survey by CMR-Nepal itself concluded that nine out of 10 social media users had received misinformation in the last week, mainly through Facebook, YouTube and X. During the recent protests, the spread of rumours confirmed the magnitude of the problem: false reports circulated about vandalism at the Pashupatinath temple, about alleged demands to declare Nepal a Hindu state and about the burning of the home of a former prime minister’s wife. Some users even shared the private addresses of political leaders, leading to threats and attacks, a practice known in Internet slang as doxxing.

2.3. Political ephemerality

Platforms reproduce the presentism of the 24-hour cycle, generating peaks of attention that rarely last over time. Although networks amplify and facilitate immediate coordination, they make it difficult to maintain a focus on structural problems.

Without continuity, digital protests tend to dissolve into a succession of episodes with no common thread. Ephemerality, in this respect, erodes the ability to translate the energy of the digital street into stable political structures.

In India the feminist movement following the 2012 Delhi gang rape (also known as the Nirbhaya case) showed the enormous power of social media to channel outrage and bring hundreds of thousands of people to the streets. Years later, hashtags such as #MeTooIndia succeeded in making testimonies visible and opening up previously non-existent public debates. However, several studies have documented that this initial energy tended to dissipate quickly: the cycle of attention on social media was concentrated in a few days or weeks, while sustained change depended more on institutional reforms and organised action by civil society groups than on digital conversation. This pattern explains why figures such as Natasha Badhwar, co-curator of Genderlog (a collaborative website on gender-based violence in India), preferred to first publish a reflective blog or newspaper column before moving the debate to Twitter.

3. Possible signs of change

It is in the everyday uses of technology that networks are built that, in times of crisis, can take on an unexpected political role. Social media should be understood as a digital public sphere. Nepal is an exceptional case that, while not reversing the dominant trend, does offer signs that are worth following closely.

3.1. New connectivities

Several governments are moving towards more centralised Internet models, with national gateways that concentrate traffic control and facilitate blocking and surveillance, similar to the Chinese model. In 2023 Nepal approved a cybersecurity policy that included a National Internet Gateway, designed to centralise access to the network and exercise greater state control. What alternatives are there?

3.1.1. The Bluetooth revolution and mesh networks

Bluetooth is a technology that seemed to have exhausted its uses, but it has found a new role in crisis contexts: providing resilient communication in the face of blockages and blackouts. Meshnetworks allow each device to act as a node, transmitting data to the next one, so that no telecommunications tower or central server is needed. One’s own phone can be used to connect to other nearby users and, by adding nodes, a mesh is created that can sustain communication even without the Internet.

In Nepal this possibility materialised with Bitchat, a messaging app created in a weekend by a small group of developers, including Jack Dorsey, founder of Twitter. The app recorded more than 48,000 downloads in a few days, allowing local messaging via Bluetooth without the need for phone numbers or a network connection.

Something similar occurred during the 2019 protests in Hong Kong, where AirDrop, Apple’s feature for sharing files between nearby devices, became a key tool for distributing messages and pamphlets without relying on the Internet. That ability to circumvent both censorship and blackouts was later reduced when Apple introduced an update in China that limited open reception of AirDrop to just 10 minutes.

3.1.2. VPNs, from being used to hide illegal actions to gaining worldwide adoption

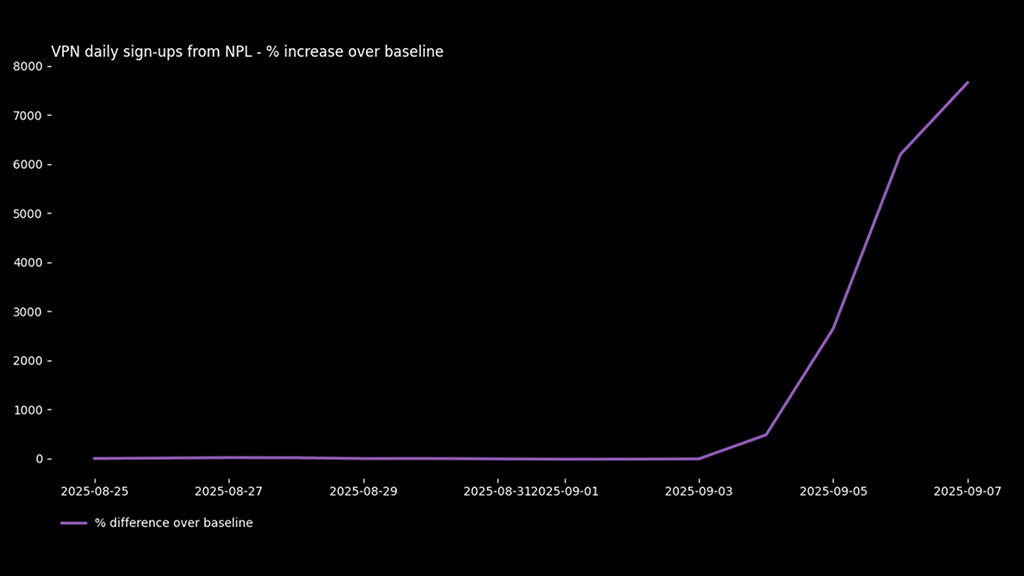

For years, Virtual Private Networks (VPNs) were associated with anonymity for illegal activities. Over the past decade their use has spread as a tool to protect privacy and circumvent blocks. By encrypting the connection and redirecting it through external servers, they allow users to hide their location and bypass geographical blocks or government censorship. In Nepal, following the September 2025 blockade, downloads of Proton VPN grew by 8,000% in only a few days.

Figure 6. Daily VPN logs in Nepal (% increase over average)

This pattern is repeated elsewhere: in France, when Pornhub was blocked, VPN signups skyrocketed by 1,000%; and in the rest of Europe, the introduction of age verification measures to restrict minors’ access to pornographic content points in the same direction: a widespread increase in the everyday use of VPNs.

3.2. Platform diversification

The digital ecosystem in Nepal reflects a high degree of concentration, as in the vast majority of countries. According to Data Reportal (January 2024) there were 13.5 million active users on Facebook, 10.85 million on Facebook Messenger, 3.6 million on Instagram, 1.5 million on LinkedIn and 466,100 on X. This dependence on a few global platforms turns social media into ‘choke points’, single points of control where a block or corporate decision can immediately disrupt communication for millions of people.

Diversification of platforms would pave the way for an ecosystem less vulnerable to censorship or centralised manipulation. Ideally, we should move towards a landscape where there are more niche applications designed for specific functions rather than platforms that concentrate all social interactions. Networks such as Letterboxd, for movie reviews, or Strava, for sharing fitnesshabits, are good examples.

The other lever is interoperability, understood as the ability of different platforms to communicate with each other. Combined with social graph portability (the ability to transfer one’s network of contacts from one application to another), this would allow users to maintain their social connections even if they change services or an application is blocked.

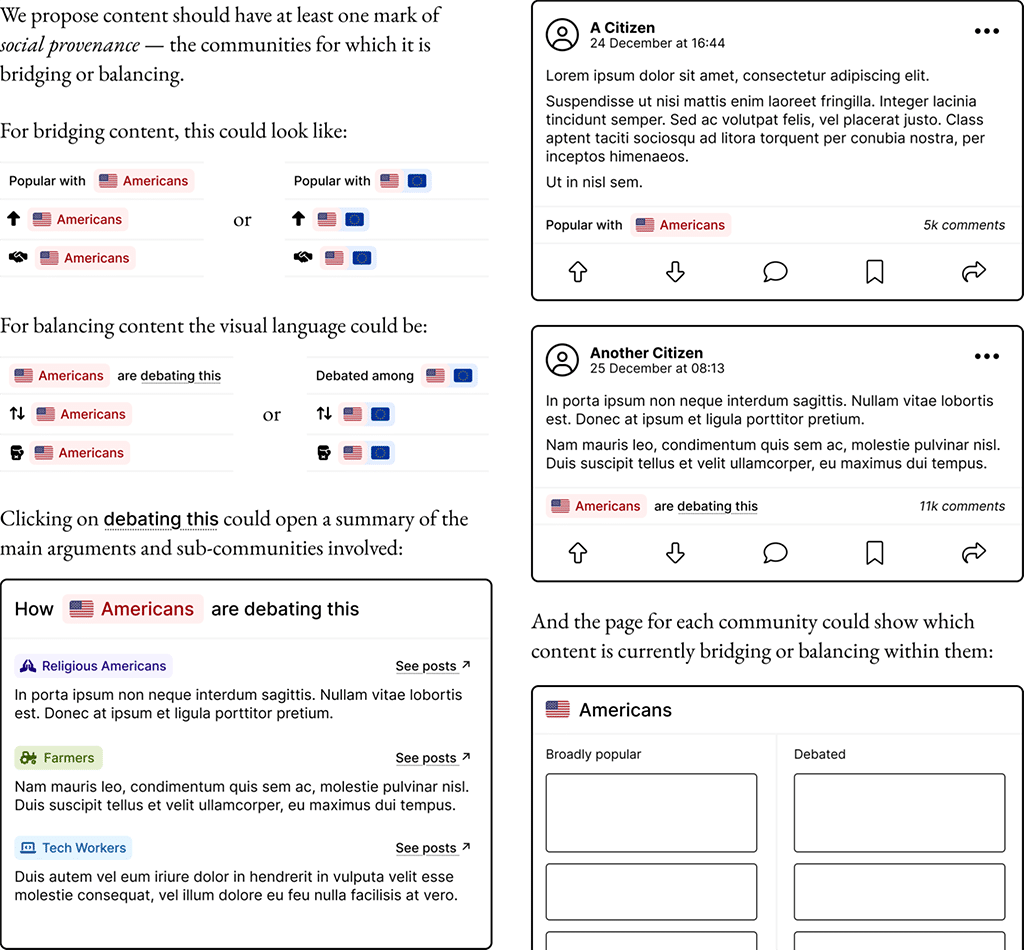

3.3. Platforms for consensus building: bridging and balancing

Most social networks are designed to maximise attention through feeds. The move of thousands of young Nepalese to Discord showed, albeit chaotically, that conversation-centred environments allow for different dynamics: less passive consumption and more need for debate and moderation.

Most participants agreed on rejecting corruption, inequality and the country’s political elite, which led to an agreement on the need for an alternative leadership. But the consensus also clashed with deep historical divisions. Territorial decentralisation, the core of Nepal’s transition to federalism since 2015, remains a source of political tension, entangled with ethnic and regional divisions. The constitution recognises three levels of government under principles of cooperation and coexistence but, in practice, powers are fraught with ambiguities: states claim legislative autonomy, while the federal government retains strong control. These disputes reflect the long history of centralisation around the Hindu Brahmin/Kshetri elites in Kathmandu versus the demands for recognition and self-government by Madhesi, Janajati and Dalit communities.

Experience has shown that conversation-centred networks can generate minimal consensus on shared problems, but they also expose the difficulty of negotiating identity and territorial conflicts that have plagued Nepalese society for decades.

This limitation is linked to a problem of temporality and design. On Discord, much of the stability depended on volunteer moderators, who filtered messages, contained calls for violence and organised conversations, without being prepared to do so. The moderators on platforms such as Reddit and Discord are informal political agents who ensure order, but without institutional recognition.

Faced with these limitations, some projects have sought other design frameworks. The most cited is Pol.is, a social network developed in Taiwan that incorporates two principles:

- Bridging: this consists of giving more relevance to content that receives support from different communities. For example, if two opposing ideological groups agree on a statement, that statement rises in visibility.

- Balancing: this ensures that all relevant communities are represented in the debate, preventing minority voices from being invisible. This encourages internal pluralism, even within the same group.

The authors of Prosocial Media have proposed incorporating this logic into the platform interface. Their idea is that each post should show indicators of whether it is acting as bridging or balancing, accompanied by tools to explore which subgroups support or reject a statement. This type of design would make the health of the conversation visible and give more weight to consensus than to extremes.

Figure 7. Proposed prosocial interface

Conclusions

What comes next?

In Nepal the coming months will be characterised by instability and doubts about the legitimacy of the process. The digital appointment of an interim prime minister does not solve the underlying problem, which will have to be resolved by the new leaders emerging from this process. It is likely that a timetable for new elections will be announced in the coming months, along with constitutional reforms to respond to the demands of the protesters. Among the most prominent figures is Balen Shah, the Mayor of Kathmandu, who is very popular among young people. He refused to stand as interim prime minister but has support within the movement to be a candidate in the next elections.

The challenge for Shah, Karki and other emerging leaders is to convert their popularity into parliamentary capacity. They need a party that can field enough candidates to achieve a legislative majority. They also require militant structures in rural areas, where electoral logistics are more complicated. Added to this is ethnic and linguistic fragmentation, as well as the persistence of patrimonialist networks, which require the presentation of local candidates with whom communities feel represented.

At the same time, a broader regional scenario is emerging. There is a wave of youth-led protests in several Asian countries such as Bangladesh, Indonesia and Sri Lanka. Some observers are beginning to talk about an Asian Spring. As seen in the Arab Spring, social media has the potential to turn local outbreaks into transnational movements, making it easier for a protest in one country to inspire and fuel others in the region.

It is striking to note that, from 2012 to today, the trajectory of these platforms has led further away from democracy rather than bringing people closer. At the time, it was thought that social media could expand the public sphere and strengthen collective action; today, the evidence suggests that their designs prioritise fragmentation and conflict. There are no solid reasons to believe that the current design of large networks can improve social cohesion or democratic functioning.

In the coming months it will be of great interest to review the recordings from Discord’s servers to identify which moderation dynamics, Discord features and informal organisational techniques worked and which did not in order to inspire other countries about what practices might be useful and what mistakes should not be repeated.

[1] The author would like to thank Mario López Areu for his comments and revisions.