Original version in Spanish: América Latina frente a un trienio electoral decisivo (2017-2019).

Theme

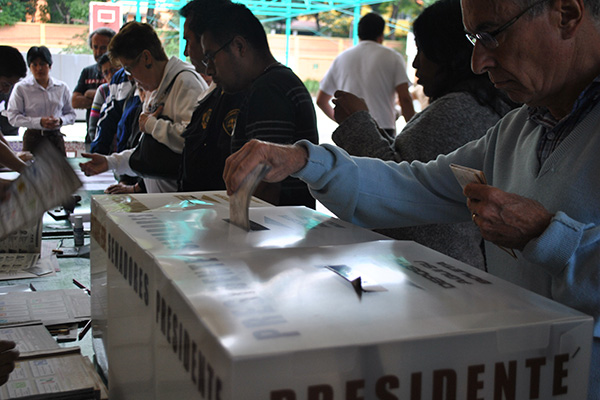

In November 2017 Latin America begins a long and intense electoral period that will last until 2019 and during which 14 countries will hold presidential elections. At stake is the adjustment of the region’s economies to the new international context and the confirmation –or not– that Latin America is experiencing a general change in political tendency.

Summary

The elections that will take place in Latin America between November 2017 and the end of 2019 will serve to determine whether or not the current change in political scenarios and equilibriums will be consolidated (the so-called ‘shift to the right’ –or to the centre-right– that has been referred to often since 2015), and if the new governments arising from the polls will possess sufficient strength and political will to tackle the structural economic reforms necessary for the region to adapt to the newly emerging global scenario, that of the 4th digital revolution.

Together with corruption and the need for higher levels of transparency, the axis of the political debates in the Latin American elections of the coming three years will focus on the struggle between those parties and leaders who advocate reform and those who embody alternatives opposed to such changes and transformations.

The Latin America of the coming decade will take shape, politically and economically, over the course of these elections in which the predominant ideological tone of the region will be defined, along with its capacity, or lack of it, to face these new global scenarios and their concomitant economic and commercial challenges.

Analysis

Latin America is now immersed in an electoral triennium (2017, 2018 and 2019) that will be decisive in determining the future political and economic course of the region in the coming decade. During these three years there will be presidential elections in Chile and Honduras (2017), Costa Rica, Paraguay, Colombia, Mexico, Brazil and Venezuela (2018), and El Salvador, Panama, Guatemala, Argentina, Uruguay and Bolivia (2019). In 14 of the 18 countries where democratic and pluralist elections exist, the Head of State will be renovated via the poll booths. In addition, in Cuba it is believed that Raul Castro will step down from the presidency in February 2018.

The Latin America of the 2020s will be shaped over the course of the coming triennium (2017-19). After the ‘neoliberal’ consensus of the 1990s, the ‘turn to the left’ of the past decade (a heterogeneous and diverse shift that did not occur in the same way in all countries involved), Latin America could be entering a moment of transition, and experimenting with ‘another shift’ –this time in the direction of the right (or, to be more precise, to the ‘centre-right’)– with a pragmatic and reformist character, of which Mauricio Macri and, perhaps, Sebastian Piñera could be considered representative examples.

This redesigning of the Latin American political map coincides and overlaps with the current regional economic crossroads and the numerous challenges it poses for adapting institutions and economies to the new world now taking shape, that of technological change and the 4th digital revolution. The governments that arise from the polling booths and the parliaments that come together as a result will need to undertake profound modifications and structural changes in search of stronger competitiveness and higher productivity for their economies now trapped in a double downward spiral of weaknesses: economic (due to weak GDP growth) and political (governments, in the majority of cases, lacking strong social backing, sufficient legislative support and political will to give impulse to a reform agenda).

Latin America: elections, economy and reforms

The reforms of the 1980s and 90s gave way to Latin American economies that were stronger, more trustworthy and more stable. Nevertheless, the reformist push exhausted itself during the last decade (hibernating, perhaps, during the economic bonanza) and in the current situation the risk is that the region will become trapped in chronic stagnation (or very weak growth, which the bonanza foreshadowed), undermining the gains in poverty reduction made in recent years. According to the IMF, Latin America and the Caribbean will collectively grow 1% in 2017 and 1.9% in 2018; this is, beyond a doubt, a recovery with respect to the negative growth of 2015 and 2016 and, at the same time, a moderate expansion (excessively moderate). Latin America benefits from the recovery of Argentina and Brazil but, as the chief economist of the IMF for the Western Hemisphere, Alejandro Werner, recognised, ‘the march resumes again, but at a slow speed’.

The numbers confirm the present trend since 2013: most countries (excepting the prolonged and progressive collapse of the Venezuelan economy or moments of deep recession, limited in time, as in Brazil, Ecuador and Argentina) do not find themselves immersed in economic crisis (not even in a progressive growth slowdown) but rather they are trapped in a dynamic of weak or low growth. From the economic point of view, Latin America has experienced a five-year period of economic inertia out of which it has not been able to pull itself given it has failed to undertake internal structural reforms. Between 2003 and 2013 Latin America experienced undeniable economic bonanza: rapid growth until 2008, negative growth in 2009 and slow deceleration or stagnation in the current decade. From 2012 the region has had four years of slow growth (2012, 2013, 2014 and 2017) and two of negative GDP growth, or contraction (2015 and 2016).

In the present economic situation (2017-19), the central problem of the region is not that it is growing negatively (growth has been positive and will continue to be so) or that growth is slowing down (it is increasing with respect to past years). The real problem is weak regional expansion, which lags far behind the figures that would make possible a significant reduction in poverty and inequality, which would require, in addition to efficient public policies, GDP growth of around 5%. Yet the weak expansion is on its way to transforming into a structural characteristic. Without reforms to make the region more competitive and productive it is highly unlikely that the longed-for acceleration will ever take place (beyond only temporary recovery spurts), leading, in the best of cases, to a Latin America perennially trapped on an insufficient growth path (slightly above 1% but far below the desired 5%).

Into this delicate moment flow the political-electoral and economic dynamics of the coming triennium. The change in the economic cycle through which Latin American countries are now passing has had as one of its principal consequences the exposure of the region’s weaknesses, which remained hidden during the bonanza (2003-13). The boom was not taken advantage of in its totality (despite socioeconomic gains) to resolve the many pending tasks Latin American countries still face.

To break the tendency towards stagnation or mediocre economic growth implies putting in place structural reforms with a wide political consensus to guarantee their sustainability and continuity over time. Reforms are needed to improve competitiveness and productivity through public policies which favour investment in physical (infrastructures and logistics) and human capital (education) and the diversification of production and export markets, while at the same time providing incentives for innovation and entrepreneurship to add more value to exports.

To implement such a reformist plan requires political will and strength. From this point of view, another problem facing the region is the lack of consensus on what reforms to adopt and how to implement them. The growing political polarisation and de-legitimisation and fragmentation of political parties does not contribute to the forging of wide consensus around the type of required structural reforms. The opposite is occurring and, for this reason, the political struggle in the coming three years will pivot and turn upon those forces, parties, movements and leaderships that propose the beginning or continuation of such transformations and those who oppose their implementation. The electorate, finally, will have to choose, in the majority of cases, between these two options: those that are disposed not only to conserve but also deepen the reforms pushed to date by governments like those of Enrique Peña Nieto in Mexico, Mauricio Macri in Argentina or Michel Temer in Brazil; or those who aspire not only to stop this reformist process but even to roll it back. This is the case of Andrés Manuel López Obrador in Mexico, the PT and part of the left in Brazil or the Kirchnerism of Argentina.

The electoral axis of reformism versus anti-reformism

What occurred in the recent legislative elections in Argentina, and the moves which were followed by the government of President Macri, after a clear victory of the coalition supporting him, are a sample of what is to come in the elections now underway and in those which are on the way: the implementation of a reformist program or its blocking.

The campaign for the legislative elections in Argentina coincided with the exhaustion of the reform impulse that the Macri government had begun in 2015 and continued during 2016. Such reform projects were partially sacrificed for the best results in the elections last 22 October. The Cambiemos (‘let’s change’) coalition was victorious in these polls and the strong backing that Macri’s executive received opened up the possibility of a second wave of reforms with very defined characteristics. First, this has implied a reinforcement of the continuity of the gradual reformism in Argentina: since December 2015 the government has opted for a gradual transformation to avoid tensions and further outbreaks of social protest. Secondly, the electoral victory has favoured the launch of four new reforms affecting: (1) the labour market (increased flexibility); (2) fiscal matters (adjustment of the State and provincial government budgets); (3) pensions (including an increase in the retirement age); and (4) education (focused on the secondary level).

As in Argentina, along with the issue of corruption, the axis upon which the political-electoral struggle of the coming three years will turn will be the reform/anti-reform debate. This will define the dynamic of the elections in the two regional giants, Brazil and Mexico. The different forces that competed in the Mexican elections of July 2008 will position themselves again in favour of, or against, the reform programme (and its possible deepening and continuity) that has been pushed by Enrique Peña Nieto (the ‘Pact for Mexico’ which reached reform zenith between 2012 and 2014). The project will be defended –and proposed for an extension and a broadening of scope– by the candidate of the PRI, especially if the current Secretary of Finance, José Antonio Meade, is chosen as the candidate to embody this model of change and transformation. But other opposition parties, like the centre-right PAN and the social-democratic PRD (now allied with the Citizens Front), will also support the reforms. These groups have been allies of Peña Nieto in the reform process and they will likely not diverge too much (particularly those of the PAN) from what has been the central objective of the current administration.

In contrast to the continuity of the reform programme represented by the PRI, the PAN and to a large degree also the PRD, the MORENA party of Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) embodies a diametrically opposed position: anti-reformism and a reversal of the changes either introduced in the current six-year mandate, or initiated somewhat timidly during the period of the former PAN President, Felipe Calderón (2006-12). The energy reform is a particular target of the MORENA leader who up until now has been ahead in the polls. AMLO aspires to review the legislation which opened the energy markets to foreign investment and has promised to hold a referendum on the reversal of this reform.

In Brazil, the corruption issue (crystallized in the Lava Jato case and its offshoots) will hang over and permeate the presidential election campaign of 2018. But the debate will also embrace the possible defence or rejection of the reform plans of President Temer (reforms which, ironically, were begun in a more moderate way by the government of Dilma Rousseff). Temer has pushed a package of structural transformations to regain the confidence of investors and to put the country back on the path of growth after two years of recession. First, the government chose to freeze public spending to contain the deficit; then it approved a package of flexible labour laws in order to stimulate labour market; and now it seeks to modify the pension system. This programme has been backed by the legislature and, from within the government, by the PSDB, the party now emerging as the favourite to dispute the second round of the presidential elections with Geraldo Alckmin (Governor of São Paulo) or with João Doria (Prefect of São Paulo), the two most likely challengers.

Against the continuity of Temer’s reforms, now in the hands of the PSDB, Lula da Silva is attempting to become a candidate, although the weight of the scandals surrounding him and his implication in current judicial proceedings will possibly block his candidacy. If this happens, his party, the PT, will claim Lula’s legacy of prosperity and bonanza as a counterpoint to the austerity of Temer. When the former President has appeared in the streets to support the protests against the current administration, the sensation he has generated, and not in vain, is that he will raise the banner of anti-reform, as suggested by his own words: “We want not only for Temer to leave, but also to stop the reforms put into place by his government, and that the people elect their president at the polls”.

In Chile, on the other hand, what is at stake in the elections of November/December 2017 is a struggle between two different strains of reformism. One is embodied by the official Fuerza de Mayoría (Force of the Majority), with Alejandro Guillier as its candidate, and aspires to carry forward and deepen the changes introduced under the management of Michelle Bachelet, which injected a social element into the liberalised Chilean economy (fiscal reform, free university education, constitutional reform and reform of the public pension system). On the other side, the centre-right opposition, linked to the Chile Vamos alliance and led by the former President Sebastián Piñera, is pushing a more ‘liberal’ reform package, include a cut in public spending, in search of economic efficiency to recover the lost path of strong expansion and to undertake a profound modification to the transformative principles pursued during the Bachelet period (2014-18).

Guillier has tried to revive the fear of the right as the vehicle of a ‘neoliberal’ programme that will suppress the ‘social benefits’ produced by the current government’s reforms. In the words of Guillier: ‘If we only get economic growth, this will accentuate the concentration of property, wealth and income, and this could generate even more social mobilisation’. For his part, Piñera has focused his government programme on pursuing fiscal austerity through the ‘budgetary reassignment’ of ‘poorly evaluated programmes’, which supposedly will lead to budget savings of US$7 billion, a foundation upon which to promote solid economic growth.

One way or another, the rest of the presidential elections of the triennium now underway (2017-19) will implicitly pit reformist programmes against anti-reform postures. In Costa Rica (February 2018) the centre of the debate will turn upon the transformations required to combat the high levels of fiscal deficit that have weighed upon the country’s development since the beginning of the century. In the same way, in Colombia (May 2018) there will be much discussion in the campaign of the FARC peace process which has polarised the country, as revealed by consultative vote in 2016. But sooner rather than later the candidates and the forces backing them will have to put on the table specific projects for reactivating an economy which has still not taken off. In fact, the IMF has just reduced its Colombia growth projection for 2017 from 2.3% to the currently expected 2%. In 2019 the Argentina that has just given an important vote of confidence to Macri will have to re-evaluate the reformist programme of the President, who will very possibly seek re-election.

Conclusions

Latin America is about to experience three years (2017-19) of high intensity electoral politics with elections scheduled in 14 countries. These include a number of important election dates, along with some of special significance (like Chile, Colombia, Mexico, Brazil and Argentina) in a double sense (political and economic).

From the political point of view, the elections of this triennium could confirm, nuance or belie the so-called ‘turn to the right’ (to the centre-right would be more exact) that the region began in 2015 when Macri defeated the Kirchnerist candidate Daniel Scioli in the Argentine presidential election, and when the MUD won the legislative elections in Venezuela. This new political-electoral trend was strengthened by the defeat of Evo Morales in the February 2016 referendum and by the removal of office of Dilma Rousseff in Brazil. Still, electoral victories like that of the Ortega block in Nicaragua in 2016 or of Alianza País in Ecuador in 2017 have transformed this supposed ‘turn’ into more of a centre-right predominance than into a global, generalised Latin American transformation. The possible victories of Piñera in Chile and Juan Orlando Hernández in Honduras, of the PRI in Mexico and of some toucan (of the PBSD) in Brazil could confirm this change in tendency towards the centre-right. Nevertheless, it also cannot be ruled out that the populist left (of Andrés Manuel López Obrador, for example, in Mexico) might win some elections, or that the ‘Bolivarian left’ will be re-elected in Venezuela and Bolivia, or that certain marginal ‘outsider’ candidates will emerge who are extremely critical of the status quo (like Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil), in a development similar to that which occurred in the US with Donald Trump.

From the economic point of view, at stake in these election is the future –or lack of one– for broad and deep structural economic reforms in the countries of the region that would prepare Latin America for the new international context in which commercial success, economic expansion and social improvements (reduction of poverty and inequality) come to those economies with the higher levels of productivity and competitiveness, and in which efficient and efficacious states and administrations put into place public policies that incentivise innovation and diversification, devote investment to physical and human capital, and work for the insertion of Latin American countries into global value chains.

Rogelio Núñez

Journalist specialising in Latin America