Original versión in Spanish: El COVID-19 en América Latina: desafíos políticos, retos para los sistemas sanitarios e incertidumbre económica.

Theme1

This paper analyses how Latin America is confronting the coronavirus crisis and the political, health and socio-economic consequences the spreading pandemic may inflict on the region and its constituent countries.

Summary

COVID-19, having emerged in Asia, has shifted its epicentre to Europe and the stage is now set for Latin America (and Africa) to play a prominent role in the next phase of expansion. The pandemic is entering a region that has advantages for combating the disease: it is learning from others’ experiences and is taking drastic steps well before its Asian and European counterparts. It also has clear disadvantages however. First, part of South America, although not Mexico, Central America and the Caribbean, is heading towards the southern winter –something that theoretically favours the spread of the virus–. Secondly, against a background of weaker economic growth, it confronts the crisis equipped with poorer tools, essentially involving inadequate health infrastructure, in the midst of an economic slowdown with politically weak governments and little scope for increasing public spending.

Analysis

What will be the impact COVID-19, or coronavirus, on Latin America, its societies, its governments and its economies? Will it be very different to what has happened in the rest of the world or will it be possible to discern some type of regional response, beyond the limitations that exist in many countries stemming from public health systems starved of resources? The coronavirus pandemic that paralysed China between December and March and has been afflicting Europe since February is now taking off in Latin America. Given the way the disease unfolds, however, everything suggests that in a few weeks, when China has overcome the crisis and the EU may see the pandemic in abeyance, COVID-19 will be undergoing rapid expansion in a Latin American region that, at its more southerly latitudes, will be heading towards winter.

More than 15,000 cases have been recorded in Latin America. At the time of writing (Monday, 30 March, at 12:00am), there has been a rapid increase compared with the preceding two weeks, as shown in Figure 1.Figure 1. Numbers of infected cases and deaths on the American continent

| Country | 14 March 2020 | 30 March 2020 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infected | Deaths | Infected | Deaths | |

| USA | 2.340 | 50 | 142.746 | 2.489 |

| Canada | 200 | 1 | 6.320 | 65 |

| Brazil | 151 | 0 | 4.256 | 136 |

| Chile | 43 | 0 | 2.139 | 7 |

| Ecuador | 26 | 1 | 1.924 | 58 |

| Mexico | 15 | 0 | 993 | 20 |

| Panama | 36 | 1 | 989 | 24 |

| Dominican Republic | 11 | 0 | 859 | 39 |

| Peru | 38 | 0 | 852 | 18 |

| Argentina | 34 | 2 | 820 | 20 |

| Colombia | 16 | 0 | 702 | 10 |

| Costa Rica | 26 | 0 | 314 | 2 |

| Uruguay | 4 | 0 | 304 | 1 |

| Cuba | 4 | 0 | 139 | 3 |

| Honduras | 2 | 0 | 139 | 3 |

| Venezuela | 2 | 0 | 119 | 3 |

| Guadeloupe | 5 | 0 | 106 | 4 |

| Bolivia | 10 | 0 | 96 | 1 |

| Martinique | 6 | 0 | 93 | 1 |

| Trinidad and Tobago | 2 | 0 | 78 | 3 |

| Paraguay | 6 | 0 | 64 | 3 |

| French Guiana | 6 | 0 | 53 | 3 |

| Aruba | 2 | 0 | 50 | 0 |

| Guatemala | 1 | 0 | 34 | 1 |

| Barbados | 33 | 0 | ||

| Jamaica | 8 | 0 | 32 | 1 |

| El Salvador | 30 | 0 | ||

| Bermuda | 22 | 0 | ||

| Haiti | 15 | 0 | ||

| The Bahamas | 14 | 0 | ||

| The Cayman Islands | 12 | 1 | ||

| Saint Martin | 11 | 0 | ||

| Dominica | 11 | 0 | ||

| Saint Lucia | 9 | 0 | ||

| Grenada | 9 | 0 | ||

| Guyana | 1 | 0 | 8 | 1 |

| Suriname | 8 | 0 | ||

| Curaçao | 8 | 1 | ||

| Antigua and Barbuda | 7 | 0 | ||

| Puerto Rico | 3 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| Nicaragua | 4 | 1 | ||

| Anguilla | 2 | 0 | ||

| Belize | 2 | 0 | ||

| British Virgin Islands | 2 | 0 | ||

| Saint Kitts-Nevis | 2 | 0 | ||

| Saint Vincent & the Grenadines | 1 | 0 | ||

| Total without US-Canada and the Caribbean | 2.999 | 55 | 15.371 | 362 |

| Total | 433 | 4 | 16.437 | 2.916 |

Source: drawn up by the authors with data from Worldometer COVID-19 Coronavirus Outbreak.

The spread of coronavirus and its arrival and expansion in Latin America need to be viewed from three interrelated perspectives that have a mutual bearing on one another: the political, the health related and the socio-economic. Their effects in Latin America involve an increase in economic uncertainty that runs parallel with the political and social tensions as the pressure on the administrations in general, and on health systems in particular, ratchets up.

(1) A stress test for governments and a leadership test for presidents

The spread of the pandemic through Latin America is going to have an initial impact with political ramifications, in addition to the predictable economic, social and health implications. The crisis comes at a time of profound weakness in the majority of the region’s governments, which in recent years have failed to provide an adequate response to the social demands of the emerging middle classes. And they have failed to do so precisely in one of the areas set to be most tested in this crisis: public services, especially health services. Together with economic stagnation and the existence of inefficient administrations riddled with corruption, the poor state of these public services (not only in health but also in education, transport and public safety) accounts for the growing and widespread disaffection unleashed at the end of 2019 in a series of popular protests that forced numerous governments in the region to change course (Ecuador cancelled an austerity plan and Chile embarked on a process of constitutional change) and even in one case (Bolivia) caused it to fall.

These governments will have to confront the coronavirus crisis while shackled by state apparatuses suffering from acute functional problems (underfinanced and, in some cases, short-staffed, lacking resources and training). From a political point of view, many administrations have a paucity of social leadership (Chile), face a new economic crisis of enormous dimensions (Argentina), find themselves coming to the end of their electoral terms (Peru and Ecuador), face the prospect of a highly polarised election campaign (Bolivia) or have extremely weak public administrations (most of Central America and the Caribbean) or are suffering from acute institutional and economic decline (Nicaragua and Venezuela) or run failed states (Haiti). The two great regional powers (Mexico and Brazil) will be most affected by the spread of coronavirus. Brazil is already the country with the greatest number of infections, while as far as Mexico is concerned, one of its great risks is its proximity to the US and its rapid rate of propagation of the disease.

Added to this is the non-existence of any effective supranational coordination. First, the Council of South American Defence, which is part of UNASUR, is afflicted by the same terminal crisis as its parent organisation. Secondly, the Pan American Health Organisation (PAHO), which like the OAS seeks to bring together the Pan-American system, is currently playing a very limited role. From next week PAHO will send support missions to those countries that ‘incur the greatest risk, such as Haiti and Venezuela. The list also includes Suriname, Guyana, Nicaragua, Honduras, Guatemala, Bolivia and Paraguay, as well as the islands of the eastern Caribbean. To date, however, no interregional or hemisphere-wide mechanism has been triggered to tackle the problem, which will be dealt with at the strictly national level, as in most parts of the world.

Despite all this, its geographical distance and isolation have so far worked in Latin America’s favour and its governments have been able to benefit from the experience of what has befallen Asia and Europe. This has helped the authorities to react early and take drastic measures sooner. Peru, with 71 cases, is the country that has taken the strictest measures. On 15 March the government led by Vizcarra announced a general quarantine, as well as the closure of its borders for 15 days to combat the pandemic: the exercise of constitutional rights relating to personal freedom and safety, the sanctity of the home and freedom of assembly and travel around the country have been curtailed.

With 45 cases, Argentina suspended classes at all levels and cancelled flights to Europe, the US and other countries with high rates of exposure. Classes were suspended in Chile before reaching 75 cases. Uruguay is notable for its rapid response: it suspended classes with only six cases. Also noteworthy in this regard are two Central American countries that, aware of the weakness of their health systems, have triggered protection measures with only one case (Guatemala) or none at all (El Salvador). The Guatemalan President, Alejandro Giammattei, placed meetings of more than 100 people in quarantine and suspended classes at all levels, while the Salvadoran leader, Nayib Bukele, ordered the civil protection authorities and the Ministry of Health to ban assemblies of more than 75 people and persuaded the legislative assembly –where the opposition wields a majority– to approve a national state of emergency for 30 days.

With 10 cases, the interim President of Bolivia, Jeanine Áñez, prohibited entry into the country for travellers arriving from China, Korea, Italy and Spain, suspended classes until the end of March and banned events involving more than 1,000 people. In Ecuador, after confirmation of the second COVID-19-related death and 28 cases, more measures were announced such as a ban on the entry of foreigners by air, land and sea. Border crossings were also closed, and mass public events were cancelled.

Colombia, with 24 recorded cases, closed the border with Venezuela and blocked entry to any foreigners who had been in European or Asian countries in the previous 14 days, while Colombians returning from these places need to submit to 14 days of quarantine and public events involving more than 500 people were cancelled. In the Colombian case, the closure of borders with Venezuela will certainly tend to aggravate the effects of what until now has been the greatest regional crisis, namely migration.

In Mexico, with 41 cases of infection, the government announced a series of measures to offset the spread of the coronavirus epidemic: the Easter holidays have been brought forward and extended to run from Friday 20 March to 20 April, entailing the suspension of classes for more than 30 million students. There has also been the suggestion that events involving more than 5,000 people should be cancelled and the recommendation that non-essential activities be suspended, with working from home encouraged between 23 March and 19 April.

In Brazil, despite having the largest number of infections, the pace of decision-making has been slower, given a certain degree of scorn for the illness on the part of President Bolsonaro. After his visit to Mar-a-Lago to meet Donald Trump, four members of the official delegation, among them the Press Secretary, Fabio Wajngarten, and the Ambassador in Washington, Nestor Forster, tested positive. The President himself was tested, although after a period of confusion he announced the result as negative. Following a major increase in the number of infections, the federal government has decided that each state and city should be responsible for taking the steps it deems appropriate. For now, it seems that the leader is not willing to impose measures of a general scope: Bolsonaro has even rejected the decision of the Brazilian Football Confederation (CBF) to suspend its competitions to limit the spread of the infection, and has accused the CBF of succumbing ‘to hysteria, and I don’t want that’.

Owing to the scale of what is happening and the Latin American tradition of presidentialism, the various leaders have adopted a conspicuous public role and taken on considerable protagonism, as well as direct oversight of the looming crisis. It is therefore set to be a test of leadership for a group of governors whose popularity and social support was already wavering (the Chilean President, Piñera, has an approval rating of just 10% in opinion polls, for example). Furthermore, in many cases they lack a protective net in the sense that these countries do not have effective or efficient administrative and health systems. This extreme personalisation of the way the crisis is handled is a risky gambit: on the one hand it has the virtue of creating high-profile leadership around a recognisable paternal figure who serves as a nexus and anchor for society at a moment of great uncertainty. On the other hand, it exposes the President to a clear risk: in the event of the situation deteriorating, all the fallout will land on his shoulders, aggravating the current problems of institutional disrepute and ungovernability that afflict Latin American countries. Argentina is a special case given the undercurrent of confrontation between the President, Alberto Fernández, and the Vice-president, Cristina Kirchner. For Fernández, successful management of the crisis would enable him to consolidate his role as the leader of the government.

The coronavirus crisis will also leave its mark on elections, falling as it does at a relatively busy electoral time. The pandemic has already caused the municipal elections in Paraguay to be postponed: ballots to appoint mayors and members of town councils to serve for the 2020-25 period, due to be held shortly, were put back to 8-28 November, and the period for parties to choose their candidates for mayors and town councillors was switched from 12 July to 2 August. The same cannot be said of the second round of municipal elections in the Dominican Republic due to go ahead this Sunday, in a country that as yet has very few cases but is due to hold a presidential election in May when the situation may well have deteriorated. Similarly, between April and May, when the pandemic may be reaching a peak in Latin America, a presidential election is scheduled in Bolivia (3 May) and a referendum on the constitutional change in Chile (26 April), when winter will be approaching in South America. Finally, the two latter were postponed. The possibility of postponing the referendum is already being discussed, and the same applies to the municipal election in Uruguay scheduled for 10 May.

(2) The health scenario amid the prospect of coronavirus

In the event that the COVID-19 outbreak in Latin America and the Caribbean spreads, the impact could be considerable, with the possibility of the health services being overwhelmed by massive demands for hospital care, particularly specialist services and intensive care. The region has both strengths and weaknesses when it comes to dealing with the spread of the virus. Prominent among the strengths are the time that has been bought and the lessons acquired over the last three months. The temporal buffer has been achieved thanks to the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans and the distance from events unfolding in Asia and Europe effectively forming a holding barrier. This has gained precious time and ensured that mistakes have not been repeated (drastic decisions have been taken earlier and strict control measures put in place).

The demographic structure also helps, with predominantly youthful populations, something that in principle should tend to reduce the number of acute cases. Lastly, and despite the increasingly urban nature of Latin America and the fact that the best and most efficient health services are clustered in the capitals and main cities, the lower densities of the less populous regions work in favour of social distancing and consequently help to slow the spread of the infection.

PAHO has recommended that countries intensify their COVID-19 preparation and response plans in anticipation of new cases appearing, and said that, ‘for several weeks, countries in the Americas have been preparing for the possible importation of cases of COVID-19… There are measures in place for detecting, diagnosing and caring for patients with the disease. A strong emphasis on stopping transmission continues to be an important objective while recognising that the situation may vary from country to country and will require tailored responses’.

The region faces the pandemic with several deficiencies, however, particularly shortcomings in health infrastructure and financing capacities. All its health systems aspire to universal coverage, but in practice most offer only partial coverage, as a 2019 report from the London School of Economics makes clear. Only Costa Rica and Uruguay meet the WHO recommendation that medium and medium-high income countries invest 6% of their GDP on healthcare. Mexico and Peru barely reach half the figure. And while some countries have lengthy and first-hand experience of combating infectious diseases such as chikungunya, zika, dengue fever and, in the case of Mexico, influenza A (H1N1), which has forced them to improve their public health surveillance systems, most have few laboratories with the ability to test samples to detect cases in under 24 hours, or centres or institutes for conducting field research into those infected with the virus, which would provide them with the autonomy for detecting it and acting accordingly. It is not so much a matter of research into the creation of vaccines as working on treatments that would enable the virus to be eradicated or its spread to be slowed.

Given that the key to tackling COVID-19 is not to focus on preventing its inevitable arrival but rather to prepare to restrict its spread appropriately, an adequate response involves having sufficient resources available: strengthening surveillance, training the health services, the prevention of propagation and the maintenance of essential services to slow down the transmission and save lives. It is in these areas where the Latin American health situation, which is very uneven and heterogeneous from country to country, suffers its main weaknesses. The most serious problem is that many of the health systems in the region lack the infrastructure and resources needed to tackle the rapid spread of the new virus. Owing to the characteristics of the disease, which has a low mortality rate but is highly contagious, appropriate venues are required not only for treating patients but also for isolating them. In many countries there are acute shortages of isolation quarters in terms of isolation rooms for infections transmitted by air and the hospital infrastructure.

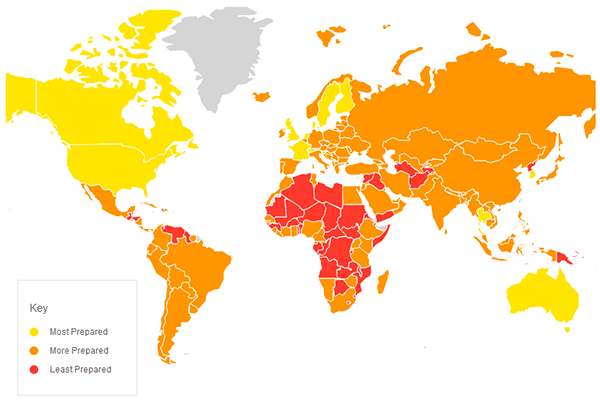

The Global Health Security Index indicates that the protective capabilities of these systems are, in general terms, middle ranking, with four countries being classified as ‘worst prepared’ (Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras and Venezuela).

Venezuela is among the 20 worst-prepared nations to deal with the spread of an epidemic, while Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras and Guyana are highly vulnerable to new emergencies. The remaining countries suffer from less pronounced failings, but with their shortages of beds and emergency services their health services will be put to the test nonetheless. An article in The Lancet has pointed out that mortality rates go up in places with higher numbers of cases and when the system becomes overwhelmed. Amid the lack of infrastructure, human, technical and financial resources, the risk of healthcare overload in Latin America is greater and this is where the region’s greatest vulnerabilities lie. The number of hospital beds per 1,000 people is very low: the best-equipped countries (Cuba and Argentina) have a fivefold advantage over the least well-equipped (Guatemala emerges at less than 1), although only five of the highest-ranking countries in terms of beds exhibit high health security.

Countries that have a degree of security and equipment higher than average are in North America (the US and Canada) and the Southern Cone (Argentina, Uruguay, Brazil and Chile). At the other extreme, the most worrying situation is that of Central America, with the exception of Panama. While it does not seem to be an infection with a high rate of lethality, coronavirus is highly infectious, something that will prove to be a serious test for the health systems of Latin America; moreover, winter is approaching, a time when the virus will presumably become more active.

(3) Limitations on economic growth that, if they deteriorate, could trigger recession

The coronavirus pandemic –which has caused European and the US (as well as Asian and Latin American) stock markets to plunge, has sent raw material prices, in particular the oil price, tumbling and paralysed Chinese and EU economic expansion– is going to exert renewed and pronounced downward pressure on Latin American economic growth. The magnitude of the regional impact will depend on how long it takes China to return to normality (once it gets its own epidemic under control, as seems likely) and how the virus evolves in the US and the EU, which is now, according to the WHO, ‘the epicentre of the pandemic’.

For the time being it is thought that it will have moderate effects on Latin America, especially in comparison with Asia, but this will be determined by the duration and extent of the contagion and the type of measures governments feel obliged to take. Latin America will not be able to avoid a downturn in its economy, hobbled by the slow recovery of Chinese demand, by the acute European crisis and by a fall in US demand, all of which will translate into greater weakness in the prices of raw materials, the region’s main export. Latin American countries are already suffering from the current 2% contraction in Chinese output, with the added prospect of a more than likely European recession (the Director General of Economic and Financial Affairs for the European Commission, Maarten Verwey, has warned that ‘it is very likely that growth for the euro area and the EU as a whole will drop below zero this year and even potentially significantly’) and a halt to growth in the US, which is currently growing at above 2%.

The impact will extend across the whole of Latin America: those countries most closely tied to China will take a hit (not only due to the paralysis suffered by China but also the time it will take the country to return to normality) but similarly it will also inflict consequences on those countries more closely linked in terms of trade and tourism to the EU and the US, which are going to see their economies seize up until at least half-way through the year. In any event it is likely that exports of food will suffer less than other primary goods, such as energy and minerals.

The regional economies most directly exposed to the economic impact of Chinese decline are Brazil, Peru and Chile, due to China’s importance as an export market. Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador and Mexico are highly exposed through commodity and agriculture prices. China is the largest trading partner for Peru (23% of exports), Brazil (28%) and Chile (32%). For Argentina, which sends China 75% of its soy and meat, some experts are predicting a fall of 5% in exports, equivalent to US$3.4 billion, and a decline in GDP of between 0.5 and 1.5%. Uruguay, which is highly dependent on its exports of meat, is in a similar situation. Mexico, Colombia and the Central American and Caribbean countries depend far less on Chinese demand and the impact will hit them from the US, where Mexico, for example, exports 80% of its output. The fall in demand from China and other countries where growth has also stalled, in conjunction with that of the US and EU, will translate into falls in raw material prices (for example, copper, iron ore and oil).

Oil prices have fallen to 1980s levels. This collapse puts the vast majority of oil-producing countries into difficulty, especially Venezuela, Ecuador, Mexico, Colombia, Brazil and Argentina. The direct consequences are very clear: if the price of a barrel of crude oil falls to US$33, fracking in the Argentine Vaca Muerta formation and exploitation of the Brazilian pre-salt layer are no longer viable, because the price does not cover the costs of production. And countries like Venezuela, where crude oil exports account for more than 90% of legal export income, are hit even harder. Coronavirus has been a severe blow to Ecuador, where the budget was drawn up on the assumption of an oil price of US$51 per barrel and it has now fallen to below US$35.

The impact on Mexico is even greater: the price of Mexican crude has broken through the floor of US$25 and there are forecasts that, if the current situation is prolonged by coronavirus and the tensions between Russia and Saudi Arabia, the US$20-barrier could be breached. This is a fall that would jeopardise Pemex, which needs the average price to remain above US$50 a barrel in order to turn a profit on its operations and to continue servicing its debt, which at US$110 billion is the highest of any oil company in the world. Now the collapse in prices puts the balance of public finances at risk. Pemex’s problems have a national impact because the company’s payments into the public coffers account for 18% of the federal budget and if the rating agencies end up cutting its credit rating, this could also drag Mexican sovereign debt downwards.

Apart from raw materials, the crisis is hitting Latin American countries in other areas, such as capital flight. Since the first infections outside China were reported in the middle of January, emerging countries have suffered capital withdrawal to the tune of more than €25.6 billion, according to the Institute of International Finance. In addition to capital outflows there have been exchange rate problems. With the dollar acting as a safe haven for the global economy, Latin American currencies have been devalued. The countries hit hardest by currency depreciation since COVID-19 started spreading are Brazil, Chile, Mexico, Argentina, Peru and Colombia; in the case of the latter, the dollar reached a level of 4,000 pesos, the highest exchange rate in the country’s history. Stock exchanges in the region have also suffered, such as the one in São Paulo, where the Bovespa index plummeted 15.6% last week, when it was obliged to suspend trading four times, as it had to do again on Monday 16 March. Something similar happened with the stock markets in Mexico, Argentina and Colombia.

The evolution of the Latin American economy is therefore linked to how the economies of China, the EU and the US perform and how long it takes for the pandemic to abate. The main risk lies in the epidemic not only propagating at a faster rate –which is inevitable– but that it lasts for longer than expected. As Federico Steinberg points out in an Elcano Royal Institute ARI, ‘it is still too early to know what the economic impact of COVID-19 will be. The key will be whether the virus can be brought under control in the second quarter of the year or whether, conversely, its effects prove more long lasting. In the former case we would be looking at a moderate impact, with a V shape, which would trim the odd decimal point from the growth in global output. In the latter, the situation could be much more severe, as the OECD suggested when it posited worldwide growth being cut in half (to 1.5%) in 2020 in the worst case scenario’.

This new situation triggered by the pandemic does nothing but deepen the uncertainty already afflicting Latin American economies, which since 2013 have been going through either slowdown, stagnation or crisis.

According to World Bank figures, between 2000 and 2019 annual growth in Latin America and the Caribbean was 1.6% on average, well below other regions, including sub-Saharan Africa (3.5%). In per capita terms the figure works out at 0.56%, totally inadequate for reducing the high rates of poverty and inequality. The region started from a stagnation scenario in 2019: excluding Venezuela –whose economy contracted 35%– Latin America grew by 0.8% last year. The forecasts for 2020 pointed to growth of 1.8%, but the coronavirus crisis has put paid to this outlook: the Economist Intelligence Unit has cut its forecast to a range between -0.4 and +0.2% since its earlier prediction of 0.9%. The investment arm of Barclays Bank predicts that the Mexican economy will record a new 2% contraction in 2020, caused by the combination of three simultaneous shocks: the impact on value chains in manufactured goods due to the situation in China, the fall in tourism and the impact of coronavirus.

The COVID-19 crisis has another consequence: it pushes back yet further the possibility of accomplishing the structural reforms the region needs to enable its economies to be more productive and competitive and not get left behind by the digital revolution. Prior to this point, getting such transformations up and running had stalled because of the large number of elections that had been held over a short period (2017-19), the weakness of the governments that emerged from these elections (most, except in the case of Mexico, lacking sufficient parliamentary backing) and the marked popular response turning into street protests at the end of last year. The crisis in China, the US and the EU, plus the effects that all this has on the region, create an additional obstacle to getting structural reform programmes under way.

Nonetheless some countries, such as Uruguay and Ecuador, seem prepared to embark on this course, although in the case of the latter everything indicates that it is more a reform in terms of the current circumstances surrounding the advent of the pandemic than an attempt to resolve the country’s major structural problems. Lenín Moreno’s government announced three initiatives last week, including adjustments to spending, the size of the state and temporary contributions, new debt and a rise of 0.75% in the taxes levied on certain companies’ income.

In the case of Uruguay, the new government, headed by Luis Lacalle Pou since 1 March, has announced an increase in charges for public utilities to come into effect on 1 April. There will also be an increase in VAT on purchases made with debit and credit cards and on restaurant bills. While it is true that Uruguay has been suffering from a serious problem of excessive public spending for years (at 4.6%, it has highest budget deficit of any time in the last 30 years), this does not seem to be the time to apply an adjustment amid the prospect of coronavirus-induced global economic paralysis, especially in a region such as Latin America that seems likely to be part of the next wave of COVID-19 expansion.

Conclusions

In an interview published on 15 March in the Bogotá newspaper El Tiempo, the Colombian President Iván Duque was very clear when talking about the crisis looming over his country in particular and the region in general: ‘Coronavirus is the greatest challenge for all the health systems in the world and will be especially difficult for Latin American countries… it could overwhelm us’. The region is indeed set to face the coronavirus crisis with unquestionable disadvantages (involving manpower and goods, infrastructure and the lack of resources, above all financial resources) but also with certain elements working in its favour. With the crisis now imminent, Latin America has to make the most of its main comparative advantage to offset its structural weaknesses. And this main comparative advantage, together with a rural population that seems likely to avoid the spread of the virus due to its isolation, is time. It has bought time thanks to the fact that COVID-19 arrived in the region relatively late and when it comes to tackling the health challenge the authorities have witnessed both success stories (in China and South Korea) and mistakes (in the EU and the US).

Latin American countries lack the means, resources, technology and the capability needed to follow the South Korean example: embarking on a massive campaign to examine the population, regardless of whether or not they have symptoms and, in a context of complete transparency, administrating widespread tests to detect the virus. What the region can do is decide to take the most drastic measures as soon as possible, founded on scientific evidence and the experience of other countries that have been successful in managing outbreaks. It is a matter of ensuring this greater room for manoeuvre is harnessed in offsetting the weaknesses the region possesses in terms of human and technical resources as well as financial shortcomings.

Barring exceptions, all signs point to the majority of countries having taken more drastic and faster decisions than in the EU or the US. This is key in terms of slowing the spread of coronavirus, thereby buying time to avoid the collapse of health services afflicted by serious inadequacies. It does not however guarantee success.

Carlos Malamud

Senior Analyst, Elcano Royal Institute | @CarlosMalamud

Rogelio Núñez

Senior Research Fellow at the Elcano Royal Institute and Collaborating Lecturer at IELAT, University of Alcalá de Henares | @RNCASTELLANO

1 This paper was originally published in Spanish on 16 March 2020.