The low cost of oil may come as an ongoing relief to many economies, such as Spain’s, but it is creating political and social volatility in numerous producer countries, both among Spain’s neighbours and further afield, reliant as they are on the income from oil to maintain their youthful populations – often more than half are below 25 and lack options for the future. It could seriously harm the economies of nearby Algeria and Libya. Great care is needed. The Arab springs of six years ago were triggered in part by a rise in the price of bread. Could the fall in the oil price lead to autumns and winters of discontent?

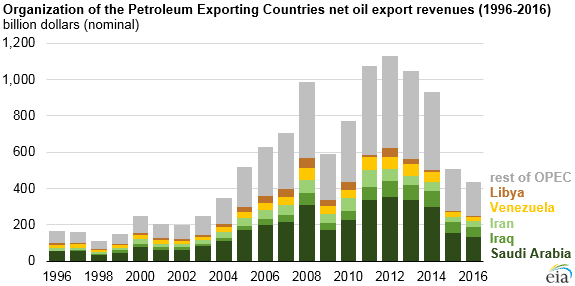

The countries that make up OPEC (Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries) have seen their income fall by 60% (from $1.182 trillion to $433 billion) between 2012 and 2016, according to a recent article published by the US Energy Information Administration. In some instances the collapse in income has been even more dramatic: from $63.9 billion to $19.2 billion in the case of Algeria and from $52.5 billion to just $2.3 billion in the case of Libya; this is without mentioning producers further afield that have likewise been affected, such as Nigeria, Angola, Venezuela and Ecuador.

Saudi Arabia’s income has gone from $368.9 to $133 billion. This fall is one of the factors underlying the promotion of Mohammad bin Salman (known as MbS, aged 31) to first in line to the throne. It constitutes not only a generational shift but also a shift of focus, because the new crown prince is the person who launched a plan to diversify the Saudi economy as a means of avoiding dependence on oil by around 2030. They have been talking about diversification across the region for more than 30 years however, without really achieving anything significant (with the possible exception of the United Arab Emirates), while pursuing a costly arms race in the Gulf. Will things be any different this time?

The failure to diversify their economies is a problem for almost all these countries, including Venezuela under the disastrous stewardship of Chavez and his ilk. Meanwhile OPEC’s leverage has waned – witness the latest fruitless attempt to cut production to raise the price – with the emergence of independent producers led by the US. It had been thought that the output of shale oil and gas would be harmed by the fall in the oil price, but North American producers have been able to adapt to prices below $50 per barrel.

Nick Butler, the well-known analyst and investor in the sector, argues in his Financial Times blog that this fall in oil prices is a structural rather than a cyclical phenomenon (although revenues will rise somewhat this year and next) and calls it “the most destabilising economic event to have hit the world since the financial crash of 2008”, albeit in slow motion. The reduction in oil revenues has already forced many countries in the Mediterranean and beyond to make further cuts in public spending and extend austerity policies, precisely when more public spending is in order to mollify their youthful and disgruntled populations. The great uncertainty represented by Algeria, pending the demise of Bouteflika, is one of the most worrying.

The effects of cheap oil can spread far and wide. The drop in Gulf countries’ revenues has meant that home-grown workers have started to be hired to do jobs hitherto undertaken by immigrants. This in turn has had a negative impact on the money such immigrant workers send back home, especially in South East Asia and countries such as India, Pakistan and Bangladesh. Such remittances fell by 6.4% last year – in the case of India by 8.9% – with local impacts that are sometimes much more serious.

Apart from other undesirable effects (such as on the investments made by Gulf states), the “geopolitics of energy” is making a comeback, as Gonzalo Escribano argues, with the only difference that it is cheaper and with other consequences. Look at what it is happening with Qatar, albeit the central factor is the confrontation between Saudi Arabia and Iran. There is also a geosocial impact, something that may have consequences for the stability of various regimes and the appeal of jihadist terrorism, even post-Daesh