There were notable attendees at the recent forum in Beijing for the One Belt, One Road Initiative, also known as the New Silk Road, but also significant absences, and delegations that lacked the seniority such an occasion called for. Conspicuous among the absences was that of India, which is opposed on sovereignty and territorial grounds (Kashmir, a source of contention with Pakistan, lies very close to the plan). Among the attendees were some 30 heads of state, including the Russian President, Vladimir Putin, and the Spanish Prime Minister, Mariano Rajoy, as well as the heads of the UN, the IMF, the World Bank and leading companies. And among the low-level delegations, that of the US, which seems to be once again erring in its stances, and the German entourage, given Merkel’s non-participation. Underlying the cartography accompanying the plan there is a whole series of latent geometrical suspicions.

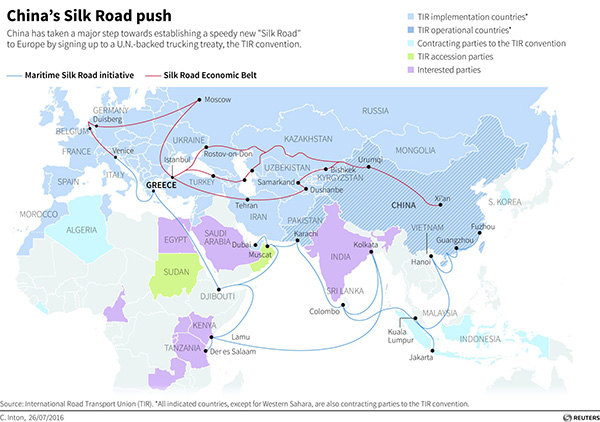

The New Silk Road is a megaproject extending several decades into the future and involving the construction of roads, railways, ports, oil and gas pipelines and other infrastructure to connect China to Central and South-East Asia, Europe and Africa by land and sea. A total of 60 countries are involved. The ‘project of the century’ was launched by the Chinese President, Xi Jinping, in September 2013 for two main reasons: internally, to find an outlet for the surplus capacity and production of steel, cement and other outputs of Chinese industry and construction, and to develop 15 inland regions, each of which has devised its own complementary plan. The external reason, both geopolitical and geoeconomic, is to open up and bring markets closer; they are aware of the fact that, beyond e-commerce and e-products, such markets still require geographical proximity and means of transport to cut the geographical distances that are so crucial to the movement of physical goods. It is what Alessia Amighini calls ‘a new geography of trade’.

A trillion dollars’ worth of investment is envisaged, although there is a certain amount of scepticism about how this will actually manifest itself.

The unfolding of the plan has coincided with something unforeseen when it began four years ago: the vacuum that a Donald Trump-led US is leaving in Asia by withdrawing from the Transpacific Partnership (TPP) and adopting a generally protectionist stance. It is highly significant that Trump refers to ‘America First’ and is seeking to launch a major internal (albeit much-needed) infrastructure plan, also to the tune of a trillion dollars (less than the New Deal), while China endeavours with its own infrastructure plan to bolster half the world and secure a new form of globalisation in which it wields more power. Because ultimately what the New Silk Road constitutes, as an editorial in the Financial Times argues, rather than a development project is a ‘stimulus for trade’, at a time when trade is stalling.

Naturally, and despite the scepticism, the prospect of the business to be done enticed many governments and companies to the Beijing forum, anxious not to miss the boat. But many harbour misgivings about Chinese intentions. The most conspicuous is that of Putin, who perceives the initiative’s potential for undermining his pet project, the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), because countries such as Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan participate in both, and China is thus penetrating what have traditionally been Russian spheres of influence. Putin, who gave a piano recital at the Beijing forum, publicly described the two plans as complementing one another and announced the creation of a bilateral Regional Cooperation Development Investment Fund to promote links between northern China and the far east of Russia.

Turkey is also concerned lest the New Silk Road should undermine prospects for its attempt to create a Middle Corridor to link up with other Turkish-speaking parts of the world. This would stretch from the Caspian Sea through Turkey and Azerbaijan to Central Asia. It is a means of strengthening ties and broadening relations by harnessing new logistical and trade activity in the Turkic world, as one of its architects has put it. Kazakhstan figures in this project too.

For their part the Europeans were late in signing up to the Silk Road, despite the fact that its two main strands –the Economic Belt running through Central Asia, and the 21st century Maritime Route via South and South-East Asia– link China and Asia with Europe. They did not get on board until 2015, and now some city halls, such as those of Madrid, Hamburg and Amsterdam, among others, have alongside governments become very active in the area. Countries in the south are more amenable than those in the north; the concern among the latter, including Germany, is that China will change the rules of investment and political solidarity between member states. Above all there are misgivings about Chinese attempts to entice Eastern Europe through their regular ‘16-plus-one’ meetings. These countries see China as a counterweight to their dependence on Russia, particularly when they see a EU wrapped up in its internal problems and the challenge of Brexit. There is also significant interest in infrastructure, such as the high-speed train link from Budapest to Belgrade (yet to materialise), and the development of the Greek port of Piraeus, now under Chinese ownership. But as Martin Sandbu has pointed out, quite apart from the physical installations, Europe should participate more not only for the business involved, but also to exert more influence in defining the rules of international trade, because ‘in the end, the “software” of trade will shape what the “hardware” can do’.

China understands all this, which is why its leaders, headed by Xi Jinping, insist that the One Belt, One Road Initiative does not seek to undermine other regional projects. Thus the Beijing forum’s final communiqué advocated consultation on an equal footing, mutual benefits, harmony and inclusiveness, market-based operations and balance and sustainability, and declared itself to be in favour international trade, something absent from other summits in which the US has participated. China’s vision always extends over the very long term. In that respect they beat us hands down.