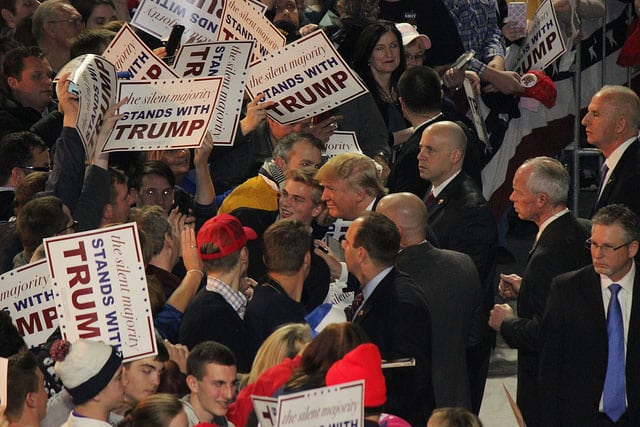

Of the various terms used to describe the mood of voters, ‘rage’ and ‘anger’ emerge with perhaps the greatest frequency in the analyses and surveys, both quantitative and qualitative, of the elections in the US. Rage has been on the rise since 2010, and it accounts for phenomena such as Donald Trump, Ted Cruz and, at the other end of the spectrum, Bernie Sanders. Cruz claimed victory in the Republican primary in Iowa, where ethnic minorities, unlike the evangelicals, play no significant role. But he is no less radical than Trump (albeit not as ostentatious or provocative), and no less spurned by the Republican establishment. It is ‘the new politics of frustration’, as Elizabeth Drew puts it, characterised by fear (economic and social, fear of the security situation, including terrorism), resentment, racism and xenophobia. Such rage is not the exclusive preserve of US society and is mirrored, under various guises, in Europe too. And there, as here, it is transforming politics.

Although what happened in Iowa, and what happens (today) in New Hampshire, is not conclusive for the primaries (the third, as Nicolas Checa points out, is important, and Marco Rubio recorded a good result in Iowa), it does reflect a deep unease on the part of US society, especially among white males, more so than among women. This political scenario is a reflection of the crisis of the middle classes. Average household income fell 12% in real terms between 2000 and 2014, and inequality has grown, despite the unemployment rate falling to 5% and signs of a degree of reindustrialisation (admittedly characterised by greater automation and use of robots).

There is less social mobility, while the much-cited American dream of climbing the social ladder has become just that: a dream. This is due, above all, to the deterioration of public education and the rising cost of private education. The differences in education –which depend on the social environment in which one was born– are a central factor in inequality, as the eminent social scientist Robert Putman has shown in his commendable book Our Kids. Among white males, those that have not been to university tend to vote for Trump or Cruz. They see immigration (today essentially Latin American) not so much as a threat to their jobs (many are unwilling to engage in certain types of employment) but as exerting downward pressure on wages and as a cultural threat. Meanwhile there are people who are frustrated by their inability to find employment in keeping with their qualifications, university graduates who make up the bedrock of support for Bernie Sanders, a self-defined democratic socialist. Up to 84% of young Democrats voted for him in Iowa, although their turnout at the caucuses was lower than in Obama’s first campaign in 2008. The new politics also work against Hillary Clinton, as seen in Iowa, although few doubt that she will emerge as the Democratic candidate.

This “angry vote” is wielded by the biggest losers from the situation, and it is paradoxical that so many should lend their support to Trump, a winner by definition, albeit one who is distanced from “Washington”, which serves as shorthand for the State, professional politicians and the establishment, a factor that works in his favour. They also distrust Wall Street and the big banks. They fear for their futures and those of their children. And what they support, rather than Trump and Cruz as politicians, are the stances they maintain, with simple messages in a society that has become polarised.

Religion has shed some of its importance in the US, but none of the candidates dare to declare themselves atheists or non-believers. George W. Bush based his victory in 2000 on enlisting the support of evangelicals. The latter have lost some influence, although they still matter, as seen in Iowa. Trump has alienated them. Ted Cruz is one to a radical degree, and even Hillary Clinton has had to speak about her religion and beliefs for the first time –she describes herself as a Methodist– quoting the Sermon on the Mount.

Cruz and Trump tap into the anger that the ultraconservatives harbour against their own Republican Party for its failure –despite being in effective control of Congress since 2010 and completely in control since 2014– to curtail immigration and dismantle the healthcare programme known as Obamacare, which has steadily become more important. Also in the background is a wing of the Tea Party, now less prominent, but still influential. But whatever happens in the primaries these messages should not be overlooked; nor should the fact that the US, like Spain and like a good deal of Europe, has entered a new phase.