Is nostalgia something negative? Not necessarily. But in our time, even more so than in earlier times, it is very easy to manipulate politically. Remembering times past, said Marcel Proust, does not mean remembering times as they were in the past. The past also reinvents itself because, as Antonio Machado pointed out, ‘neither tomorrow nor yesterday are written down’. European society and politics, according to a recent survey by the Bertelsmann Foundation, are now dominated by the nostalgic who think that the past –without specifying which– was better than the present. But if this is the case, it is due to something.

It is not a neutral sentiment, but one that has consequences. As Simon Kuper has pointed out, referring essentially to Brexit, if the revolution that some aspire to is set to ‘recreate the glorious past’, there is no need to waste time in planning for impending developments such as climate change and artificial intelligence, which are partly already here. The boom in nostalgia may be intimately linked to the economic crisis and the collapse in the expectations for a better life felt by large segments of Europe’s societies, together with the memory of care-free earlier years. Nostalgia is a reaction to anxiety and fear, to the known and to the unknown. It is a sign that the present is neither understood nor liked.

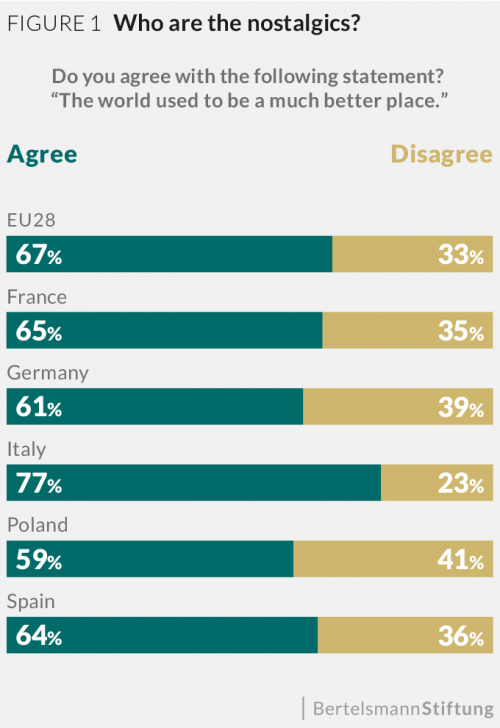

The word ‘nostalgia’ has Greek roots, from nostos, returning home or to the homeland, and algia, meaning pain but also a sense of longing. Nostalgic people today are a majority in Europe: 67%, according to the Bertelsmann survey, think that the world used to be a better place. Nostalgia is only slightly more notable on the right than on the left. It is correlated to a negative attitude towards immigration. Young people tend to be less nostalgic than their elders, although the most pronounced are those aged between 36 and 45. In Spain, those aged 16-25 are evenly split. Men feel more nostalgic than women.

The report encompasses the large EU countries: Germany, France, Italy, Poland and Spain. It excludes the country where nostalgia has already had political effects, namely the UK. The most nostalgic turn out to be the Italians (77%), while the least nostalgic, understandably, are the Poles. Spaniards (61%) are at a mid-point, behind the Germans and the French.

In terms of European integration there are no major differences between the nostalgic and the non-nostalgic, although the desire to remain within the EU is greater among the latter (82%) than the former. All of them are notably in favour (above 80%) of controlling borders, but also of the free circulation of people and a more active role for the EU in the world.

Concern about the future leads to taking refuge in the past, as other studies into Europeans’ values have shown. The Bertelsmann report points out that nostalgia is a powerful political tool: ‘References to a better past are skilfully employed by populist political entrepreneurs to fuel dissatisfaction with present-day politics and anxiety about the future’, and mistrust of mainstream political elites. It is an ‘instrument for agitation’. The new nationalist-populist movements play with nostalgia, and cite the ‘decline of the [allegedly] golden age’. Of course, the view of the past depends on the present, or the future, from which it is viewed. Things were not the same looking at them from 1928 or from 1930. Nor did Europe look the same in 1943 as it did in 1960, or, coming closer to our day, in 2006 as it did in 2011, or even, many would say, in 2019. Today the standard of living throughout the world is much higher than 100 or 30 years ago (Pinker, Rosling). There is, however, a crisis of the future, a crisis of expectations.

Five years ago Angela Merkel pointed out that Europe, the EU, accounts for 7% of the world’s population, 25% of its economy and 50% of global social spending, which is unsustainable. Perhaps what underlies this fever of nostalgia is the fear and anxiety of Europeans that they are losing influence in a world that has ceased to be Eurocentric –something that will never return– and doubts about whether it will be possible to maintain the European way of life, with its social safety net.

Rightly understood, rather than hankering after a largely imagined past, nostalgia could serve as a means of building a better future. ‘A better kind of reflective nostalgia can enable a lament for the past to help us build a different future’, according the philosopher Julian Baggini. Politics should not ignore the past. It can learn from it. Nonetheless, while making constant use of the rear-view mirror, it needs to look forwards.