One of the main questions in tackling the issue of immigration lies in its very definition. Currently, the EU seems to consider it more as a matter of social and international security rather than a humanitarian plague. Still, there are many other factors that seem to slow the achievement of a good and proper solution.

Since the 2013 Lampedusa tragedy, Italy decided to accept the responsibility of both preventing irregular immigration and – most importantly – rescuing human lives. Despite domestic critiques about the cost of the operation “Mare Nostrum”, the efforts actually managed to reach notable results: 140,000 people rescued. The operation involved five naval means, ten aircrafts (helicopters and drones) and up to 1000 military personnel, with a cost of more than 10 million euros monthly. An extremely high amount for a single country like Italy, but according to the Dublin Regulation, the Member State from which the asylum seeker enters the EU has the responsibility of hosting him – and that clearly penalizes Italy.

Further Italian pressing on a more effective involvement of Brussels brought to the realization of the current operation named “Triton”. Started officially in 2014, in the beginning the plan was intended to be complementary to the existing “Mare Nostrum” operation, but it soon took its place. For the Italian government, European intervention represented a double achievement, leading to a relief of the budgetary burden, and at the same time, diluting its responsibility in the area. Moreover, the many domestic critiques over excessive spending and according to which rescues would have represented an incentive for human smugglers undoubtedly had a relevant impact in the decision of suspending the operation.

The most controversial issue laid in its budget: 2,9 million euros per month were allocated at the beginning, promising in an increase with the introduction of the Internal Security Fund. The main objective of “Triton” is the surveillance of EU southern borders in order to prevent the threat of irregular immigration, even if according to the former FRONTEX Executive Director Gil Arias Fernandez, “saving lives will remain an absolute priority”; the limits of intervention – within 30 miles off Italian shores, while “Mare Nostrum” included international waters – should not be ignored as well. Hence, objectives have been changed into others more “limited”, as the very same budget can prove: two-third less than “Mare Nostrum”, with the difference that the number of participants now is more than one. All this without the use of ships equipped for rescuing purposes.

While it is true that the problem is not the absence of a proper mechanism of prevention, the real issue at stake is the lack of competences at the EU level. Here the question of immigration is still one of the most controversial, the main reason of which is the importance of such a domaine reservé that represents a key element in domestic policy, especially during political campaigns. The whole rescuing and humanitarian machine also means a huge economic turnover that attracts human smugglers and mafias on both endings of the routes. The current Libyan situation, with its many warlords and extremist factions, could not provide any more favourable condition for them to obtain finance from the many desperate people coming from different parts of Africa, a turnover estimated to be 34 billion dollars every year. What is true is that most of migrant boats depart from ports controlled by Islamist militias; Libyan Coast Guard has denounced the lack of means for preventing departures, adding that they had already called for aid without any replies. The EU is clearly hesitant, for there is no certainty of knowing into whose hands this aid may fall. On the Italian side, the recent “Mafia capital” scandal is another example of how an emergency can be exploited, in which a dangerous mix of mafia mobsters and corrupted politicians run its own business by rigging contracts and making money from the construction of refugee centres.

In the last special meeting of the European Council, security concerns have prevailed over humanitarian needs. While it is true that the budget has been tripled and assets increased, engagement rules are still the same. Member States are trying to show some interest in the issue by committing more assets in the operation, but no agreement over redistributing and hosting refugees have been reached: this is especially the case of the United Kingdom, where the upcoming elections and the presence of extremist views have induced Prime Minister Cameron to make clear that no refugee will be admitted. The European Council also underlined the intention of destroying vessels used by smugglers: something difficult to obtain at the moment, as it would require international support as well as the approval and cooperation of Libya’s internationally recognized government.

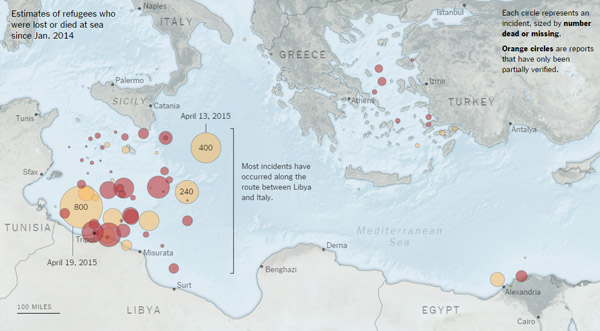

This refugee crisis has shown one the main gaps in European common policy to be filled in a Union founded on the respect of human dignity, liberty, equality and human rights. Saving lives still represents the main target, but it is necessary to act at the bottom of the question: there is the need to assist, strengthen and cooperate with local authorities of failed states like Libya where to begin a real state-building process, and not just palliate the emergency. Once again, we are looking at the short-term effect, while we should focus more on the long-term solution. The last tragedy in which more than 800 people died is the smoking gun that efforts have not been enough.