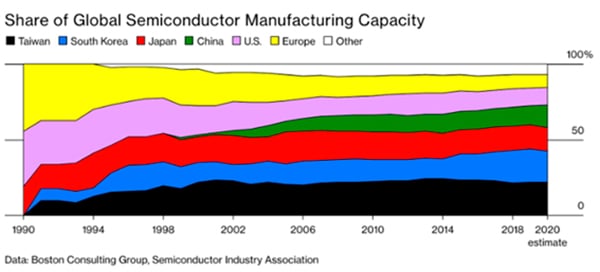

Let’s go back to the 1990s. It was a time when the EU dominated the mobile phone industry (2G and 3G), had pre-eminent manufacturers of handsets –Nokia was a world leader–, built PCs and accounted for 30% of global manufacturing output of semiconductors, the essential silicon chips. In 2000, when it approved the flawed Lisbon Strategy (flawed because it set intermediate targets that were not compulsory and failed to provide the resources to attain them), the EU proposed to turn itself in 10 years into ‘the most competitive and advanced knowledge economy in the world’. Twenty years later, the more conservative goal is to become ‘a world leader in innovation in the data economy and its applications’. These days, in a much broader global market, it makes less than 10% of chips and aspires to a 20% global market share by the end of the decade, it imports almost all of its mobile phones, it has fallen behind in 4G technology and is dependent on others in 5G and has lost its lead in connectivity, not to mention its super-dependency on US and even Chinese platforms. What went wrong?

Europe undoubtedly missed the boat, which sailed laden with a substantial cargo of industry and services linked to the Internet (invented at CERN, the European Organisation for Nuclear Research) and its offshoots, smartphones (the first, the Apple iPhone, went on sale in 2007), and the data economy, now in the hands of large non-European operators, including Amazon, without which many European companies would not have been able to get off the ground. Europe meanwhile, despite the desire of the Commission and governments to fill the void, lacks a unified big data market. Foreign big tech firms have been quick to take advantage of this Balkanisation of European data.

Many European companies have to go to the US in search of funding, because Europe, the EU, lacks a single market for venture capital, or a Capital Union. Member state markets are insufficient, even if reformed, something Spain is trying to do with its Start-ups Law. It is not that there is no Silicon Valley in Europe, or ever will be. This may not even be necessary, since the model is changing. The EU has no equivalent of Sand Hill Road, the Palo Alto address of numerous venture capital investors, earning it the nickname of the Wall Street of the Valley. Then of course there is Wall Street itself and NASDAQ for high-tech companies. But aversion to financial risk still predominates in Europe. Failure is not seen, as it is in the US, as a way of learning for the next entrepreneurial adventure.

Europe does not fare so badly in the area of basic research. Some of the research into COVID-19 vaccines originated in Europe (the UK and Germany, more slowly elsewhere) but strictly speaking, as things stand, there is no purely European vaccine. According to a report from the Center for Security and Emerging Technology (CSET, at the University of Georgetown in Washington DC), the US has lost its leadership position in scientific literature in recent years –one way of measuring this field– not only to China but also to the EU. Some studies suggest otherwise, and in the field of Artificial Intelligence (AI), for instance, the Center for Data Innovation, with an index based on a range of parameters, calculates that the US still leads with 44.6 points out of a possible 100, followed by China with 32 and the EU with 23.3. The Asia Centre argues that Europe fails in five aspects essential for developing a powerful AI sector: an abundance of data, innovative entrepreneurs, talent (high-quality AI scientists and technicians, many of whom have left Europe for the US), an AI-friendly policy environment and well-targeted and abundant funding.

The US owes part of its success to the input of the government, especially the Pentagon, as Marianna Mazzucato convincingly argues in The Entrepreneurial State. The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), founded in 1958 in response to the Soviet Sputnik, lies behind many of the tech advances of recent decades. Rather than trying to guess the future it may be said to have invented it, ranging from part of the Internet to touchscreens, GPS, voice interfaces and other innovations, including the new mRNA vaccine system subsequently developed by Moderna, then a small company that had DARPA’s backing. Breakthroughs such as this have subsequently been incorporated into money-spinning devices and services. Steve Jobs was able to reap the benefits of these innovations. And ARPAs (without the defence element) have now proliferated in the US Administration (domestic security, intelligence, energy, recently the environment and Biden wants another to cover health issues). Hence various governments, although not the EU as such (there is a European Research Council for basic science), are studying the creation of European DARPAs and ARPAs (as is Japan), although less closely linked to security concerns. Naturally, this includes the UK, outside the EU, with its Advanced Research and Invention Agency, and Germany, with its civilian Federal Agency for Disruptive Innovation (SPRIN-D) and another for cybersecurity. How about a Spanish ARPA? As The Economist points out, however, such initiatives are doomed to fail unless they are created with the same spirit that motivated DARPA, which means few bureaucratic hurdles, minimal political interference, ample funding (DARPA’s 2020 budget was US$3.6 billion), taking risky gambles and ensuring that all work is contracted out.

One problem in Europe is the transition from scientific research and basic technology to a commercial or other kind of application, from the lab to the store. There are some exceptions. Two European companies, Nokia (Finland) and Ericsson (Sweden) dominate 5G radio and core access technology but are more expensive than their Chinese and South Korean competitors. It is a sector that Europe does not control, although it is well advanced in the installation of networks. Another shining example of European know-how are the unique and indispensable machines made by the Dutch firm ASML (each costing €130 million) for creating nanocircuits in silicon chips.

The attempt to establish or restore European digital sovereignty, or at least autonomy, has led to a host of national and Europe-wide strategies. The European Commission has launched a flurry of proposals –almost every week there is something new– including the Digital 2030 Digital Compass and Horizon Europe, to tap into the funds now available through Next Generation EU and the Multiannual Financial Framework 2021-2027. Twenty percent of the more than €2 trillion total will be spent on innovation and digitalisation over this period. It is a lot. But it is also not very much, compared with the Biden Plan in the US, or what China is thought to spend on such matters. Getting an advanced semiconductor factory (or ‘foundry’) up and running requires an investment of at least €20 billion. The German Economic Affairs minister, Peter Altmaier, wants to invest in chip manufacturing, alongside other European countries and the Commission, as in the US, with 20%-40% state funding. The European Commission has its own plan for semiconductors, where disruption to the supply chain has forced various car plants to grind to a halt. It has also unveiled plans for a European data industry. Member states have woken up to the need for Europe to be sovereign and independent, or at any rate more interdependent, in these areas.

At stake for Europe in the years ahead is the possibility of regaining control of its technological destiny or of writing it off. But this requires a thorough understanding of its failures in the past.