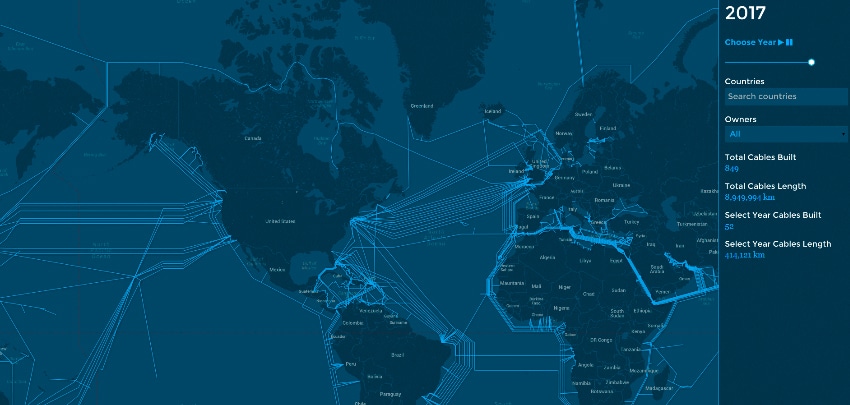

Will it be infrastructure that saves us, this time on a global scale? Will such infrastructure involve the injection of money that the world economy needs and provide the connectivity needed for everyone? Meeting in Hangzhou on 4 and 5 September, the G20 made a commitment to infrastructure and the essential connectivity it can bring to all, to mature economies, the emerged, the emerging and those that have been left behind. The writer and analyst Parag Khanna, in a generally outstanding book, refers to a connectography in a world that is going to become hyper-connected, while the Chinese president Xi Jinping talks about ‘global connectivity in infrastructure’. For Khanna, ‘the most connected power wins. States must protect their borders, but what matters are which lines they control: trade routes and cross-border infrastructures’. He cites some interesting statistics: ‘Our infrastructural matrix today includes approximately 64 million kilometres of highways, 2 million kilometres of pipelines, 1.2 million kilometres of railways, and 750,000 kilometres of undersea internet cables that connect our many key population and economic centres’. All this is without taking into account the infrastructure needed for essential connectivity: wireless infrastructure. ‘By contrast’, he adds, ‘we have only 250,000 kilometres of international borders’. But in terms of politics and identity these matter a great deal.

This global focus on infrastructure has been one of China’s obsessions during its presidency of the G20, which now passes to a Germany that is more sceptical on the issue. Various advances have nonetheless been achieved, both theoretical and practical, in this ‘infrastructure connectivity’ to which the Hangzhou communiqué refers. Recent months have seen the launch of a Global Infrastructure Connectivity Alliance Initiative, a declaration by 11 multilateral development banks regarding Aspirations on Actions to Support Infrastructure, and other more regionally-focused measures such as the Juncker Plan in the EU; there is also the Asia Infrastructure and Investment Bank, driven by a China that is in turn sponsoring its new Silk Road strategy, by both land and sea (known as One Belt, One Road). The latter is a striking example of the proliferation of new transport routes throughout the world, from the Mesoamerica Integration and Development Project for the Maputo corridor, to the economic corridor of the Mekong sub-region in south-east Asia. It will prove more difficult to build continental infrastructure in Latin America, for political reasons and because investment there is significantly lower on this arena than in Asia.

The process is neither uniform nor global. What is now being proposed is part of the improvement that the G20 is trying to foster towards an ‘innovative, invigorated, interconnected and inclusive world economy’. The infrastructure gulf that separates various regions and countries of the world needs to be bridged, not only in quantity but also in quality; this is something that interests many Spanish companies, which have acquired expertise at home and are venturing abroad now that the domestic market has contracted.

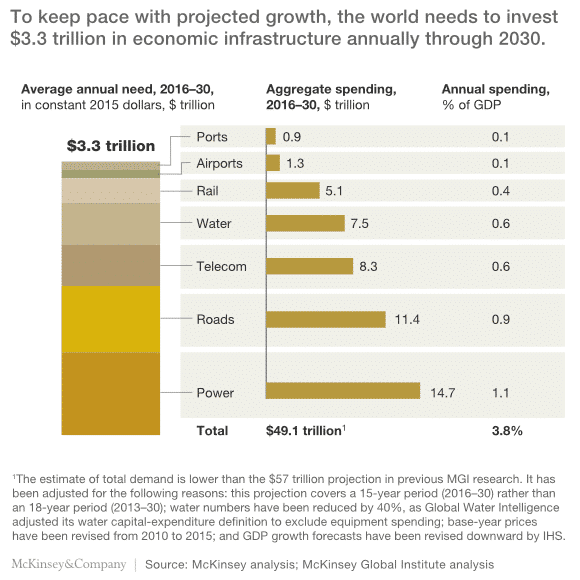

The McKinsey Global Institute has released a report arguing that although the world invests US$2.5 trillion a year on infrastructure, US$3.3 trillion is needed simply to maintain the expected rates of growth between now and 2030. Emerging economies will account for 60% of these needs, with energy networks being the greatest priority, followed by roads, telecommunications and water. According to McKinsey, if the current underinvestment persists, the world will fall short of covering its needs by 11%, or US$350 billion, a year. And the size of the gap triples if the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals for 2030 are to be achieved.

One problem is the lack of public money for these projects, hence the need to undertake more and more public-private partnerships (PPPs), even if the end-products are what may be thought of as public assets. The World Bank, the OECD and the GIH (Global Infrastructure Hub) are sponsoring ‘annotated PPPs’, and monitoring such investments over the long term. It would be a misconception to think of only roads and ports when infrastructure is mentioned because, as the McKinsey report points out, it also refers to everything that supports the new digital economy. Thus for example the extension of mobile telephony is revolutionising Africa in many ways. It also includes educational infrastructure (an area where Spain lags behind somewhat, although it leads the way in high-speed rail networks and is well positioned in broadband networks).

A global focus on infrastructure could stimulate a world economy that, as the G20 points out, is growing more slowly than expected, at a time when trade and international investment are stalling. Like so many things, however, it something that is easier said than done.