In Donald Trump’s US, but similarly exemplified by Brexit and other western societies, there is a ballot-box rebellion among a generation of working and lower-middle class white men (not women), who feel neglected and abandoned by the politics and new values that have been in the ascendant since the 1970s. Although partly socioeconomic, it is essentially a cultural reaction that is generating a new type of politics: what sociologists have taken to calling ‘identity politics’, which could lead to new kinds of intrinsically intractable problems.

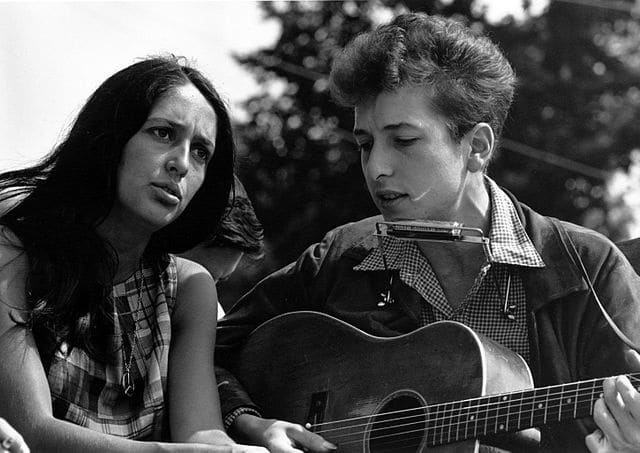

Among the cultural changes that have taken place since the 1970s are: growing equality with women, which some men have interpreted as their own diminishment; the ending of discrimination against homosexuals and the granting of gay marriage rights; increased immigration and a trend towards multiculturalism; post-materialism; the deindustrialisation accompanying globalisation; and the era of digitalisation and automation of processes, among other factors. All played a prominent role in the Trump campaign and the leave campaign in the UK, among others. It is a reaction against, for example, what the new winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature, Bob Dylan, stood for in his day.

Two renowned US-based sociologists, Ronald Inglehart and Pippa Norris, have carried out a quantitative and qualitative study of Brexit and concluded that we are in witnessing a ‘silent revolution’ of those who are overlooked in their own country amid the progressive cultural changes of the last 40 years. Arguably in a country like the US it should be African-Americans who have most to complain about given that Barack Obama, the first black President, has managed to achieve rather little for them, as evidenced by the cases of police brutality that have provoked such outrage. Instead it is white men who feel humiliated.

This is the cultural reaction theory, a rival to the economic insecurity theory, although there are clear links between the two. While such theses are still largely speculative, history is in fact capable of unleashing, over the course of more than 45 years –three generations– this type of reaction. In the medium run, however, such social and generational groups will lose simply by virtue of disappearing over the course of time, giving way to the arrival of new cohorts steeped in different values.

But for the time being with this ‘silent revolution’, or counter-revolution, the most prominent symptom of which is opposition to immigration, sometimes to people who are not very different, like the Poles in England or Mexicans in the US, we may be ‘generating our own drama’, as an Italian observer recently pointed out. Some identities are emerging the significance of which we do not understand. Thus, nostalgia for the Empire and Commonwealth (source of ‘our’ immigrants, according to many English people) may have played an important role in enabling ‘leave’ to win the Brexit referendum.

What is or what are these identities in Europe? Is it an identity based on values that are now called into question, including human rights? If it is accepted that politics is based on this kind of perception, rather than on realities, conflict is assured. Hungary, for example, a country of 10 million inhabitants and more than 2 million scattered throughout the world, without counting earlier diasporas, refuses to accept a quota of some 2,000 refugees.

It is true that Hungary experienced 1968 differently, through the lens of what happened in Czechoslovakia with the Warsaw Pact invasion and the repression that followed. It is also true that Spain was under a dictatorship, but subsequently, as the historian Santos Juliá has pointed out, Spanish society started to convulse. This is without mentioning France and its famous unrest of May ‘68, or Germany, or the counter-culture movements in the US and the protests against the Vietnam War, as well as many other social movements. Something began in 1968 that would later gather steam in the 1970s and subsequently. And this is what a section of western societies are now rejecting.

That said, issues of identity and values are not going to be settled or determined in Brussels or Washington, but rather within broader, more deeply-rooted social frameworks.